2

Elspeth Slayter; Rose Singh; and Lisa Johnson

Learning Objectives:

- To understand how critical theoretical perspectives can inform social work practice with the disability community

- To apply the model, inclusive of the planned change process, to social work practice with the disability community

- To identify elements of the model for social work practice with the disability community that may be used within one’s own professional context

Introduction

This chapter presents a model for social work practice with disability communities, which follows the social work planned change process and is informed by the theoretical perspectives of critical cultural competence, intersectionality, and anti-oppressive practice. We first review the planned-change process as a facet of social work practice. We then offer an overview of key theoretical perspectives that inform the practice model, including their application to disability social work practice. Next, we introduce a model for social work practice with the disability community and include a detailed case example following the work of a social worker and client using the planned-change process. Finally, we offer a comparison of the model to existing disability practice models.

Introduction to the Planned-Change Process

The “planned change process” is the foundation for much of social work practice in the United States that is focused on the development and implementation of an approach to change behaviors, a condition or circumstance that will improve the life of a client in some way (Kirst-Ashman, 2012). This process can be applied at multiple levels – micro, mezzo, and macro – and with a spectrum of populations. This process is one that social workers can use to plan and implement change with clients and client systems.

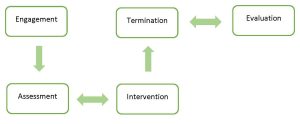

Consisting of a series of steps that can be summarized as client engagement, assessment, intervention, termination, and evaluation, the planned change process provides a basic framework from which social workers can frame their practice with clients and client systems. Although the planned change process is typically visualized as linear, it is not linear when put into practice. For example, work with a client might vacillate between assessment and intervention as the client-social worker relationship evolves and/or as new challenges arise or become clearer.

Although the planned change process is at times conceptualized differently with respect to the number of steps included, the following is a summary of the commonly used steps in the planned change process. The first step, engagement with the client, refers to the beginning interaction between client and social worker. As the relationship develops differently for every client and every circumstance, there is not a set timeframe in which engagement happens. Skills used by social workers during the engagement step include active listening, use of eye contact (depending on cultural preferences, traditions, and expectations), demonstration of empathy, and reflection on what the client is engaging in. This step is all about fostering rapport and trust between the client and the social worker.

The second step, assessment, is led by the social worker who gathers, analyzes, and synthesizes information from the client in order to develop a picture of the client’s functioning, needs, and strengths. Assessment is the foundation of the action steps that follow it. According to Johnson and Yanca (2010), there are five important activities in the assessment step: identifying the need; honing in on the nature of the problem; identifying strengths and resources; collecting client data; and analyzing all of the above information for development into an implementable plan.

The third step focuses on the implementation of an action plan that is guided by goals and objectives co-created by the client and the social worker. The fourth step, termination, takes place once goals and objectives have been met and there is no more need for social work services. This involves a situation in which the client and social worker reflect on the work that they have done together before closing out the professional relationship.

The fifth step, evaluation, may be considered important to engage in throughout the planned change process and may also be an aspect of termination. During the previous steps, the social worker is ethically mandated to always evaluate how the client is doing throughout the course of the social work process through either implicit or explicit evaluation (i.e. supervision vs. formal data analysis). However, when the goals have been met, the client and social worker should review the goals and objectives and evaluate what change did take place and what could be improved upon vis-a-vis process or content. If a change did not occur, the client and social worker should reconsider the goals and objectives to make alterations focused on achieving the goal.

History of the Planned Change Process

As critical consumers of knowledge for social work practice, it is important to note that the planned change process was developed in the context of the United States and may be somewhat culture-bound based on the era in which it was developed and who was involved in academic social work at that time. Based first in the United States social diagnosis-informed social casework model developed by Mary Richmond, this process is also informed by the problem-solving model put forth by Helen Harris Perlman (1957).

Mary Richmond is well-known as the person who developed the concept of social diagnosis, in which a person and their problem are considered within the larger socio-political context (Richmond, 1917). Richmond is also known for the development of the social casework framework in which she highlighted the importance of including clients in the solving of their problems (Richmond, 1922).

The problem-solving process builds on Richmond’s work and can be thought of as a synthesis brought together from several sources including Perlman’s background in the humanities and her philosophical reflections together with her knowledge of psychodynamics and the social sciences. In this process, the social worker supports the client in learning how to analyze problems while providing consultative education in the art of effective problem solving. Perlman had significant clinical expertise, and her process demonstrates strong emphasis on the importance of the helping relationship in direct practice (Perlman, 1957). Perlman formulated a unique cognitively focused and client-centered problem-solving process for social work practice.

Over time, these ideas were shared and further developed by social workers and came to be known as the planned change process, supplanting the problem-focused language. Though there is a dearth of information about the origins of the term “planned change process,” authors Kirst-Ashman and Hull (2010) are often credited with bringing this idea to the fore of social work education through their textbook writings on generalist practice.

Critiques of the Planned Change Process

Despite the widespread use of the planned change process, there are important critiques of the process that we must consider. First and foremost, there are always limitations to a generalist framework, which is not considered a treatment modality in and of itself. As in any consideration of practice approaches, it is important to consider who developed the framework and who has been left out of its development. Considering that this framework was created in the context of White middle-class culture, some have raised questions about whether the approach may be unsuitable for clients from other cultures or social strata. Some argue that the planned change process might be especially ill-suited to people who are thought to rely on less organized and less focused approaches to difficulties (Sue, 1981; Galan, 2001). Furthermore, it does not take into account ‘other’ ways of doing social work, such as the use of religious helping, the ways informal kin networks function, or the non-professional helping approaches found in Indigenous communities. The discipline of social work has both pulled from (e.g., family group conferencing) and ignored (e.g., suicide prevention interventions) these communities in practice over the last century (Baskin, 2016, Cox et al., 2019, Drywater-Whitekiller, 2014; Pon et al., 2011; Wexler & Gone, 2012). Along the lines of this critique is that professional problem-solving is only one approach and one that may restrict the ways in which a client tells their story, thus failing to consider alternative thinking and reflecting approaches.

Another major critique of the planned change process is that it is not data-driven or evidence-based in its origin. As Perlman developed the problem-solving model when research was not a major factor in social work practice, her supporting documentation was taken from clinical and anecdotal sources, as well as her clinical experience. In other words, when creating her model, Perlman used the now-discredited authority-based argument in her research (Gambrill, 1999). Authority-based practice is based on what is known as ‘practice wisdom’ as opposed to evidence-based practice (DeRoos, 1990).

Finally, the most recent critique of the planned change process is presented in the South African context (van Breda, 2018). In thinking about how best to apply the planned change process to post-Apartheid South Africa, in which a developmental approach to social work is noted as ideal, van Breda (2018) considers two major critiques. First, the planned change process “gives primacy to the economic vulnerability of society, and this commitment must be evident in casework for it to be regarded as ‘developmental’” (p. 77). Second, in proposing needed changes to the planned change process, van Breda (2018) calls for such a process to lift up the rights of clients while fostering the agency of clients in both their own living context and in their relationship with social workers and other helping professionals. This author suggests that change can be accomplished by “fostering a highly democratic and participatory helping process; placing the person and the development of the person, rather than the problem, at the centre of the helping process…and promoting resilience, independence, self-sufficiency, and community-connectedness, rather than dependency and worker-centredness” (van Breda, 2018, p. 77). While van Breda’s (2018) writing is focused on the South African experience, these critiques have applicability to practice in the United States as well.

Despite these limitations, the planned change process has some utility in working with clients and client systems. Our adaptation of the planned change process addresses some of the aforementioned limitations by applying a critical lens and employing concepts related to disability-positive social work practice.

Critical Perspective

The critical perspective, which stems from the work of social philosophers linked to the Frankfurt School, evolved as a response to both totalitarian and positivist thinking gaining popularity in post-WWI Western Europe (Salas et al., 2010). Since then, the critical perspective has been applied to various fields and areas of study. In social work, the critical perspective is both a lens through which we interrogate our practice within complex social structures and a guide for reflexive engagement with individuals, groups, communities, and systems.

A critical approach to social work, prompts us to examine the methods, structures, beliefs, and knowledge that inform our professional practice. This critical approach also leads us to grapple with the simultaneous roles of social work as an agent of social control and a threat to the status quo. The profession of social work, like most culturally and socially bound institutions, defaults to a position of maintaining, often unintentionally, systems of privilege and oppression. However, with intentional and ongoing critical awareness and action, social workers can act against, instead of in concert with, oppressive processes and outcomes.

Theoretical Perspectives

We highlight three theoretical perspectives that are informed by the critical perspective and are useful for disability social work practice: critical cultural competence; intersectionality; and anti-oppressive practice. These complementary perspectives emerged in social work in temporal (the 1970s and 1980s) and geographical (the United States and Canada) proximity to one another.

Critical Cultural Competence

Critical Cultural Competence

Cultural competence, a precursor to ‘critical cultural competence’ (which we define below), originated in social work as a response to the increased focus on multiculturalism that emerged in the 1980s (Nadan, 2014). Cross, Bazron, Dennis, and Isaacs (1989), Green (1982), and Solomon (1976) are acknowledged as the progenitors of cultural competence, which has become one of the most prominent constructs in social work education, practice, and research (Danso, 2018; Garran & Werkmeister-Rozas, 2013; Nadan, 2014). Cultural competence is defined as a “set of congruent behaviors, attitudes, and policies that come together in a system, agency, or among professionals and enable that system, agency, or those professionals to work effectively in cross-cultural situations’’ (Cross et al., 1989, p. 3). Cultural competence is also a process by which individuals and systems respond respectfully and effectively to people of all cultures…in a manner that recognizes, affirms, and values the worth of individuals, families, and communities and protects and preserves the dignity of each (National Association of Social Workers (NASW), 2015).

Recently, a more critical approach to cultural competence, ‘critical cultural competence,’ has emerged with the argument that “awareness, knowledge, and skills alone are inadequate for culturally empowering social work research [and practice]; they should be harnessed for social change” (Danso, 2015, p. 574). Critical cultural competence refers to “social workers’ ability to engage in high-level action-oriented, change-inducing analyses of culture and diversity-related phenomena” (Danso, 2015, p. 574). This concept also recognizes issues such as intersectionality, power differentials in the worker-client relationship, and examination of one’s social location or social position held in society based on social characteristics (Lusk et al., 2017).

Keenan (2004) further expands on the importance of infusing a critical lens into cultural competence through the idea of informed not-knowing, which, while attesting to the importance of lifelong learning, can guard against essentialism or overgeneralization. There is recognition that “knowledge is always partial, perspectival, and constructed through the lens of understanding, meaning, and interests of one’s social position” (p. 543). Using a critical lens in the practice of cultural competence includes the practice of cultural humility, which incorporates an ongoing commitment to self-evaluation and self-critique as a way of maintaining an engaged learning and an other-oriented stance (Hook et al., 2013; Tervalon & Murray-Garcia, 1998).

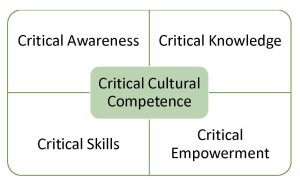

Almutairi, Dahinten, and Rodney (2015) developed a Critical Cultural Competence model “comprised of four key components: critical awareness, critical knowledge, critical skills, and critical empowerment that fall into a number of conceptual domains: cognitive (critical awareness and critical knowledge), behavioral (critical skills) and affective (critical empowerment)” (p. 318). Critical awareness encompasses awareness of cultural differences—between and within groups—and self-awareness. Critical knowledge focuses on learning with an understanding of the dynamic nature of culture. Both critical awareness and critical knowledge underpin the use of critical skills in intercultural interactions. Finally, critical empowerment attends to power imbalances in relationships and the environment. The Critical Cultural Competence model was developed with specific attention to multicultural healthcare environments but has potential for use in a variety of areas.

Application to Disability Social Work Practice

As Dupré (2012) notes, “the disabled people’s movement…affirms and celebrates the existence of disability culture as characterized by several agreed-upon assumptions: disability culture is cross-cultural; it emerged out of a disability arts movement and its positive portrayal of disabled people it is not just a shared experience of oppression but includes art, humor, history, evolving language and beliefs, values, and strategies for surviving and thriving” (p. 168). Critical cultural competence supports recognition of the personal and positive elements of disability culture while aligning with the social model of disability in its critique of ableist social, political, and economic systems. In working with individuals and families, this construct brings attention to the power dynamics inherent in many service systems, especially those engaged in involuntarily. It also helps practitioners develop competence in reflective processes related to engaging across cultures, contexts, identities, and experiences. Furthermore, critical cultural competence prompts the self-reflection and critical examination necessary to recognize one’s own biases, perspectives, and position within cultural and social systems. Finally, this construct helps us avoid essentializing disability experiences, identities, and contexts.

Limitations of this Framework for Disability Social Work Practice

There is much less application of cultural competence or critical cultural competence to disability in the literature than to other identities, experiences, and practice areas. One reason for this, as Dupré (2012) notes, is that the field of social work has not embraced an understanding of disability culture. Cultural competence and intercultural practice are most often addressed as related to race, ethnicity, language, and religion. Therefore, there are fewer theoretical and empirical explorations of critical cultural competence in disability social work to inform practice. Also, though we have seen a highlighting of disability culture by disabled people’s movements, it remains that disability is not uniformly or universally viewed as a social/cultural identity. This has implications for how identity- and culture-bound perspectives are applied when working with disabled people who do not hold disability as a cultural identity. Finally, though the ‘critical’ element of critical cultural competence attends to the notion of practitioners adopting an expert stance regarding culture, there remain concerns that the element of ‘competence’ in the construct lends itself to essentialism (Dupré, 2012; Nadan, 2014), especially as related to disability “types”.

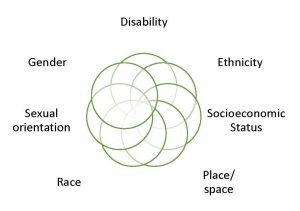

Intersectionality

Intersectionality

The history and development of intersectionality is not static and continue to shift. Kimberlé Crenshaw, an American lawyer and scholar, is credited with naming the term intersectionality. The idea and conceptualization of intersectionality, however, may be traced back further. Guy-Sheftall (2009) notes the contributions of Anna J.H. Cooper (1858-1964) to Black feminism and intersectionality, as evident through Cooper’s writings on the racism and sexism experienced by Black women in the Southern United States. Hancock (2005) outlines how W.E.B. Du Bois (1868-1963) wrote about race and class as well as race and gender, developing early ideas on how identities and oppressions existed and operated together in political contexts.

Activism and social movements led by women of color during the 1960s and 1970s further contributed to the development of intersectionality. Francis Beal and Toni Cade Bambara published work examining the interconnected impacts of racism, sexism, classism, and capitalism in the lives of Black women (Collins & Bilge, 2016). The Combahee River Collective, through their advocacy and activism, brought attention to the multiple oppressions – racism, sexism, classism, and heterosexism – experienced by their members and communities (Collins & Bilge, 2016). During the 1980s, contributions to intersectionality are linked to a number of activists, writers, and scholars including (but not limited to): Gloria Anzaldúa, Angela Davis, bell hooks, Akasha Gloria Hull, June Jordan, Audre Lorde, Trinh Minh-ha, and Cherríe Moraga (Bubar et al., 2016; Collins, 2015; Collins & Bilge, 2016; Hulko, 2009; Mehrotra, 2010).

Kimberlé Crenshaw was instrumental in bringing the term intersectionality to the forefront. Crenshaw (1989) argued that Black women experience racism and sexism in the legal system and shifted these terms to include women of color. At the time, in the legal system, racism was commonly understood in reference to men of color and sexism in connection to White women. Crenshaw (1989, 1991) brought forward that these forms of oppression were not mutually exclusive and operated together in distinct ways for women of color. Patricia Hill Collins has also contributed immensely to the theorizing and conceptualization of intersectionality. Collins (1990, 2000) proposed interlocking models of oppression versus additive models, in which multiple oppressions are not viewed in binaries (i.e., Black or White, female or male, etc.) and, instead, are considered to function together. Collins (1990, 2000), for example, highlighted the racism, sexism, and classism experienced by African American women, yet acknowledged that these oppressions also impact many other groups. In this view, using the interlocking model, oppressions exist interdependently.

While the roots of intersectionality remain in activism, social movements, and scholarship by women of color, intersectionality has expanded considerably and is now found across disciplines (Collins, 2019). Intersectionality has also developed in definition, meaning, and application over the decades (Cho et al., 2013; Collins, 2015; Collins, 2019). Broadly, Collins and Bilge (2016) describe intersectionality as an “analytic tool” and a “way of understanding and analyzing the complexity in the world, in people, and in human experience” (p. 11). Intersectionality, as Collins and Bilge (2016) note, considers “social inequality, power, relationality, social context, complexity, and social justice” (p. 53). They emphasize intersectionality in praxis, its belonging to social movements, and its connections to transformation and social justice (Collins & Bilge, 2016). Given the significance of these ideas to social work, scholars and practitioners have contributed to the understanding and applications of intersectionality within the social work profession (see, for example, Bubar et al., 2016; Hulko, 2009; Joseph, 2015; Mattsson, 2012; Mehrotra, 2010; Pease, 2010). Contemporary social work has generally integrated intersectionality as a broad term that encompasses all forms of oppression and groups of people. Not always are the key contributors and developments of intersectionality fully recognized in social work. Current and future social workers may not have an appreciation or give credit to the feminists and activists of color who brought this theorizing and work forward. Thus, an acknowledgment of how intersectionality came to be before being incorporated into social work is intentionally included in this article.

Oppression and Privilege

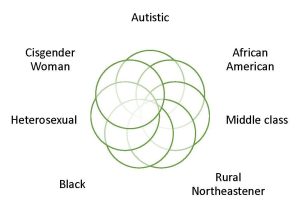

People accessing services and social workers alike have various personal and social identities that position them as oppressed and privileged. How one defines and understands themselves signifies their personal identity, whereas how others define and view them refers to their social identity (Hulko, 2009). Collins and Bilge (2016) emphasize that identity is a “starting point for intersectional inquiry and praxis and not an end in itself” (p. 101). They explain that identity can be a way to form coalitions, collective action, and transformative movements (Collins & Bilge, 2016). Coming to know and understand how identity may impact people and communities is imperative to social work practice. Oppression and privilege experienced as a result of specific identities, for instance, gender, sexual orientation, race, class, age, or disability, denotes one’s social location (Hulko, 2009). Interlocking systems of oppression, for example, racism, sexism, and ableism, position and marginalize one’s social location (Hulko, 2004). Awareness and analysis of how identities are privileged and marginalized, in addition to the interconnectedness between interlocking systems of oppression and social location, are a central component of social work practice. Ranking oppressions is often a concern that arises when future or current social workers are learning about intersectionality. Fellows and Razack (1998) describe that competing oppressions cannot be deemed hierarchical and being marginalized does not make one exempt from being implicated in the oppression of others. Fellows and Razack (1998) refer to the latter as the “race to innocence” (p. 339). Razack (1998) further explains that addressing one aspect of marginalization cannot be separated from challenging all forms of oppression, whether one is impacted by specific subordinations or not. Given the saliency of certain issues in society, it is crucial to consider the historic and current contexts of oppression.

Application to Disability Social Work Practice

Intersectionality in disability social work practice allows for a more comprehensive appreciation and understanding of a person’s and community’s experiences. A disabled person has personal and social identities, which impact their daily life and realities. Their social location further determines opportunities that may or not be available to them. Interlocking systems of oppression, such as the ableism, racism, and sexism they may experience, often exclude them from many facets of society.

While significant, the disability or disabilities people live with are not their entire being and are connected to other aspects of who they are (MacDonald, 2016). For instance, they may also be a student, a parent, a member of a faith community, and hold a particular job title or role. However, disabled persons are often defined by others through an ableist lens, placing this disability’s social identity at the forefront (Touchie et al., 2016). Using an intersectional lens, social workers may view the entirety of a person’s experience.

Limitations of this Framework for Disability Social Work Practice

Intersectional social work practice and scholarship, with a focus on disability, is an emerging area (see, for example, Johnson et al., 2020; MacDonald, 2016; Wehbi & Lakkis, 2010). Despite a recent growth in interest in disability and intersectionality, it is a limitation that there is not extensive literature to draw on to inform our work. Numerous social workers already apply an intersectionality lens in practice, and many future social workers will certainly bring considerations of intersectionality and disability to their work and contribute to this evolving area.

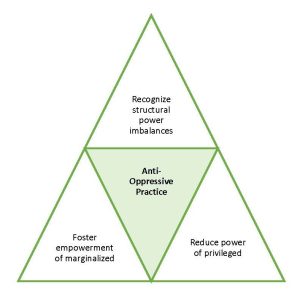

Anti-Oppressive Practice

Anti-Oppressive Practice

With a more recent introduction in the United States (Morgaine & Capous-Desyllas, 2015), anti-oppressive social work practice traces its development from radical and structural social work in Canada (Baines, 2007; Sakamoto & Pitner, 2005), critical social work in Australia (Fook, 2002; Ife, 1997; Healy, 2005, 2014) and anti-racism and anti-discriminatory social work practice in Britain (Dumbrill & Yee, 2019; Macey & Moxon, 1996; Williams, 1999). Anti-oppressive practice, as Dumbrill and Yee (2019) outline, is an “umbrella of theories and perspectives” (p. 230). As it has evolved, anti-oppressive practice has expanded to draw on additional theories, which include: feminist, Marxist, post-modernist, Indigenous, post-structuralist, critical constructionist, anti-colonial, and anti-racist (Baines, 2007, 2011; Brown, 2012) with queer and disability perspectives more recently added (Baines, 2017). By building on numerous progressive frameworks, anti-oppressive practice is positioned as a transformative approach to social work (Lai, 2017).

Anti-oppressive practice centers on recognizing and challenging power and oppression, seeking equity, inclusion, and social justice for oppressed persons, groups, and communities, while emphasizing broader political, systemic, and structural understandings and explanations of social work and society (Baines, 2007, 2011, 2017; Dalrymple & Burke, 1995, 2006; Dominelli, 2002; Morgaine & Capous-Desyllas, 2015; Payne, 1997, 2005, 2014). With social work typically focusing on individual practice and the problems of people accessing services (Baines, 2007; Sakamoto & Pitner, 2005), anti-oppressive practice moves beyond this limitation by considering the personal, cultural, and structural levels of oppression experienced by persons and communities (Campbell, 2003; Mullaly, 2010; Mullaly & West, 2018).

Understanding and acknowledging the roles of identity and social location is fundamental to anti-oppressive practice. Baines (2007) explains that identity is how a person is associated or categorized with either dominant or marginalized groups, with social location being how they are situated within the “webs of oppression and privilege” (p. 24). Oppression is rooted in the unacceptance of differences and the prejudice and discrimination of certain identities and groups (Dumbrill & Yee, 2019; Mullaly, 2010; Mullaly & West, 2018). Examples of such oppressions include ableism, racism, sexism, heterosexism, cissexism, classism, and ageism (Dumbrill & Yee, 2019). Less mentioned in anti-oppressive practice are the impacts of colonization, imperialism, or globalization in creating and shaping the power, privilege, and access to resources inherent among dominant groups (Baskin, 2016; Dumbrill & Yee, 2019; Pon et al., 2011; Pon et al., 2016; Yee & Wagner, 2013).

Critical consciousness-raising, as proposed by Sakamoto and Pitner (2005), is important to anti-oppressive social work practice. This action involves an ongoing process of critical reflection and analysis of the social worker’s assumptions, values, biases, and worldview, of the power dynamics in the helping relationship, and shifting this to empower the people and communities the social worker is engaging with, while also addressing broader social injustices (Pitner & Sakamoto, 2005; Sakamoto & Pitner, 2005). Anti-oppressive social workers aim to engage in this process of critical consciousness raising throughout their practice.

Application to Disability Social Work Practice

Anti-oppressive social work, according to Carter, Hanes, and MacDonald (2012), must recognize ableism in discourse and in practice. Ableism prevents the inclusion and participation of disabled persons in society. Recognizing multiple oppressions, including ableism, and working with disabled persons and communities to challenge these oppressions, gives a way for social workers to practice anti-oppressively (Wehbi, 2017). Building on the social model of disability, Carter, Hanes, and MacDonald (2017) propose an anti-oppressive model of disability for social work. This approach deconstructs dominant notions of disability, while centers on individual, community, and societal change (Carter et al., 2017). Specific practice skills for working anti-oppressively with disabled persons, as outlined by Carter et al. (2017) include critical consciousness-raising, deconstruction, viewing disabled persons as the experts, empathy, addressing grief and loss, reframing, advocacy, mediation, peer support, and community engagement (pp. 160-162). Anti-oppressive social work practice, according to Sandys (2017), addresses the barriers disabled persons experience when seeking social roles of importance to them, whether this is being a post-secondary student, gaining employment, volunteering, or participating in the community. Anti-oppressive social workers recognize and emphasize the valuable place disabled persons and communities have in society (Carter et al., 2017; Sandys, 2017; Wehbi, 2017).

Limitations of this Framework for Disability Social Work Practice

Anti-oppressive practice with a focus on disability is less explored in the literature despite the relevance and application of this approach in working with people with disabilities (Sandys, 2017). However, social workers seeking to practice anti-oppressively should not be limited by this lack of information. Anti-oppressive practice literature, including that centered on disability, offers ideas and ways to work alongside disabled persons and communities (Carter et al., 2017; Sandys, 2017; Wehbi, 2017). Social workers seeking to practice anti-oppressively must be up for the challenges of doing social justice social work in an ethical and meaningful way.

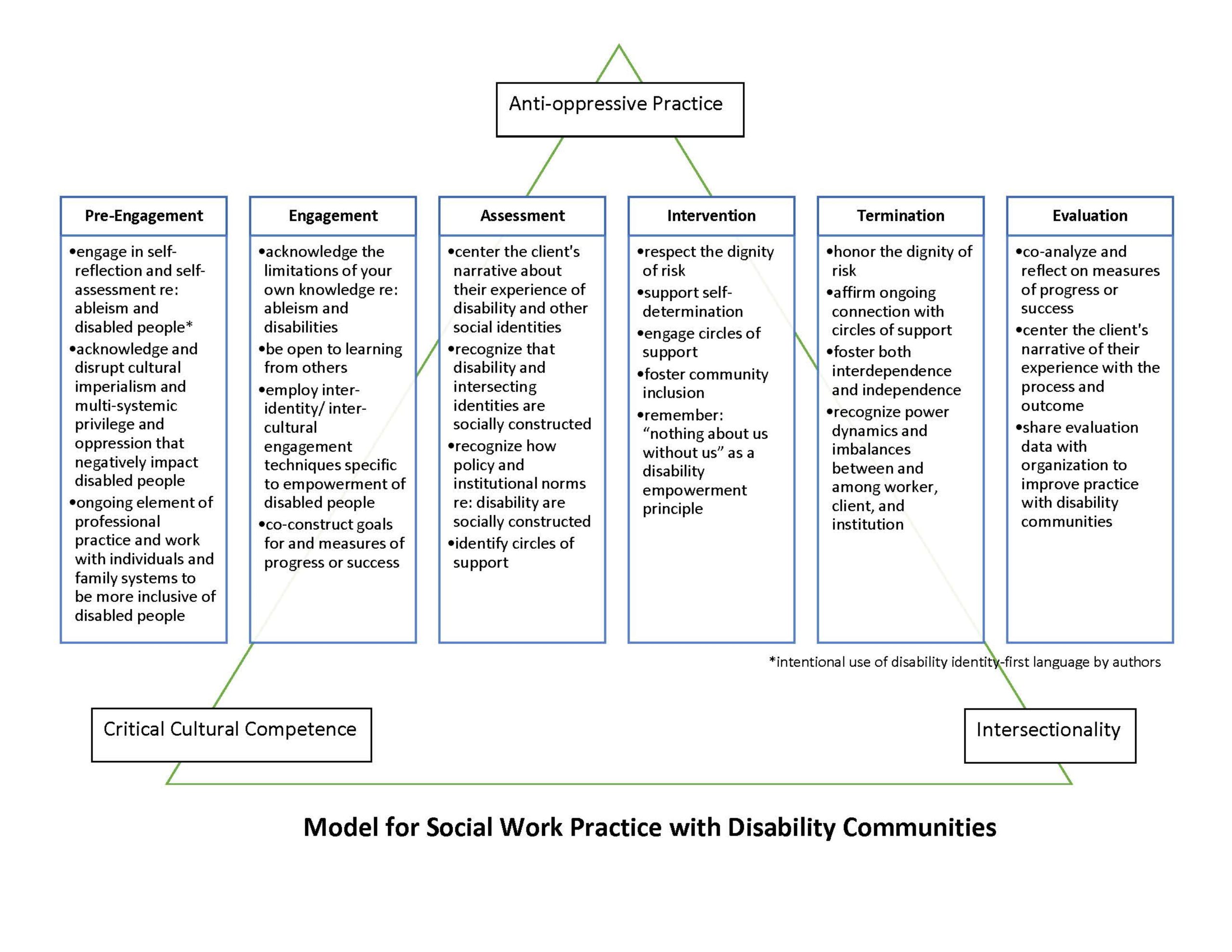

Introducing a Model for Social Work Practice with the Disability Communities

Our model views the planned change process through the lenses of the tripartite theoretical frameworks presented above, with disability-specific applications in each stage of the process.

Pre-Engagement

Pre-engagement is a step not explicitly found in other iterations of the planned change process, which typically begin with engagement. We added pre-engagement as a key initial step to highlight the importance of engaging in reflective and reflexive practice regarding one’s positionality (with special attention to intersectionalities), assessment of cultural competence, practice of cultural humility, and preparedness to engage in anti-oppressive practice.

The tenets of anti-oppressive practice call for social workers to engage in reflectivity and reflexivity about who we are as social workers, and what and how we do things (Baines, 2017). Central to that process is a consideration of practitioners’ social identities and how they may lead to privileged or oppressed positions. Considering this ‘positionality’ is vital for social workers to engage in prior to meeting clients who may have different positionalities. Reflectivity is about unearthing the actual truth embedded in what professionals do, versus just what they say they do (Schön, 1983, 1987). Reflexivity, by contrast, is the ability to look inwards and outwards to recognize how society and culture impact practice as well as how we ourselves influence practice. The reflective and reflexive social work practitioner will want to ask, “How do I create and influence the knowledge about my practice that I use to make decisions?” In embracing reflectivity and reflexivity, social workers move beyond ‘just knowing’ how well practice is going, which is a form of implicit evaluation that is subjective by nature.

Reflexivity and reflectivity tie especially well to the concept of critical cultural competence described above. Critical cultural competence posits that awareness, knowledge, and skills are not enough for doing empowerment-oriented, anti-oppressive practice (Danso, 2015). Social work practice without the use of a critical cultural competence lens may affect ineffective or low-quality services (Casado et al., 2012) and may deepen marginalization in traditionally oppressed communities, such as the disability community (Danso, 2015). The four key components of critical cultural competence are especially useful and necessary at the pre-engagement step of the planned change process, critical awareness and critical knowledge (Almutairi et al., 2015).

When thinking about critical awareness, acknowledging sociocultural differences, especially as they relate to our clients’ disability identity, is vital. Recognizing disability identities links back to our need to take an intersectional approach to understanding ourselves in relation to our clients – which is in turn part of anti-oppressive practice. Assessing our individual attitudes and values is important, along with recognizing or watching out for the potential challenges associated with cross-cultural interactions as there are a range of disability cultures present in the United States. Being able to have awareness of disability-related cultural differences is vital to the self-awareness required for social work practice with disabled people (Almutairi et al., 2015).

In particular, social workers need to be aware of the potential consequences of disability cultural diversity while also recognizing the social determinants of intersectional power relations based on disability and other social identities (Almutairi et al., 2015). With respect to the gathering and use of critical knowledge, the authors are focused on developing a conceptualization of any disability culture our client might identify with as well as gathering information about any potential communication challenges during cross-cultural interactions (which may often be between disabled and non-disabled people, for example) (Almutairi et al., 2015). At this stage, it is also vital for social workers to question their connection to and operation within the political state as it relates to disability justice (Baines, 2017).

While this pre-engagement step is framed as the initial step in the process of work with a client, the above-described types of reflective and reflexive considerations need to be engaged in on an ongoing basis as case dynamics shift and evolve by continually employing a critical lens to examine one’s own perspectives and practices as well as the structures and systems with which the client is interfacing. Also, maintaining a stance of informed not-knowing, recognizing the limitations of current knowledge and the need to engage in ongoing learning is important (Keenan, 2004).

Now, to move from the theoretical to the applied, social workers can engage in a range of considerations in the pre-engagement step as an act to disrupt cultural imperialism in the form of mainstream, non-disability justice-oriented practice (Baines, 2017). For example, the social worker should consider their varying social identities and resultant world views in a consideration of how those views might impact their work with the specific client in question. Questions to consider might include “How will my social identities impact client engagement?” “How might my world views get in the way of seeing things from my client’s point of view?” or “What social welfare system-cultural norms do I practice that might get in the way of a fair, client-specific assessment?” By engaging in this form of reflexive and reflective practice, social workers can work towards subverting dominant cultural paradigms (about who needs and deserves help and in what ways) that may, when subconsciously implemented, oppress clients (Baines, 2017).

As noted above, the planned change process in general, and the model for social work practice with the disability community in particular, may be implemented at multiple levels of practice. To demonstrate how the critical theoretical perspectives informing the model could be applied to a micro/mezzo-level social work practice situation, a multi-part case example is offered below. Though the case study primarily focuses on micro- and mezzo-levels of practice, the influence of macro-level issues is acknowledged as part of the narrative.

Example

Josie, a licensed clinical social worker, receives a referral to work with a new client, Regina. Based in an outpatient mental health center, Josie is tasked with providing Regina with counseling to address challenges she is facing with family members and work colleagues. Given that much of the agency’s current work with clients is occurring remotely due to the COVID-19 pandemic, Josie will need to utilize a telehealth platform or phone to connect with Regina.

The case file Josie reviews includes an intake form filled out by the client and records from the agency’s previous involvement in Regina’s life. Josie notes that Regina identifies as a Black woman and that she grew up in a rural area in western Massachusetts where her family has lived for generations. Josie reads that Regina is a high school graduate who tries to maintain a balance between being able to engage in meaningful work that does not put receipt of her health care benefits at risk in order to manage the care she needs for her disability, which is identified as autism. Before reaching out to Regina, Josie spends time considering how her own presence as a White, middle-class social worker from the suburbs of a major city (who also does not identify as disabled) might impact the process of building a relationship with Regina. Further, she considers how her worldview and values relate to messages she received while growing up and how this may impact her future work with Regina.

Acknowledging that history and language are powerful influencers of perspectives and practices, Josie takes time to consider the history of mainstream social work with various Black communities, which, when involved, was often oppressive. She also learns about the historical roots of formal and informal mutual social aid in Black communities that addressed the needs and fostered the resilience of community members prior to the advent of mainstream social work and in response to instances of exclusion from or harm done by dominant systems. Given what she learns about history and language influencing practice, Josie notes that it will be important to ask Regina about how she describes herself with regard to race, ethnicity, disability, and other identities, and how she understands her own experiences with service systems. Additionally, Josie happens across an article that explores the complexities of written expressions of identity, specifically whether or not to capitalize the racial identity categories of Black and White. Josie researches this further and finds that there is no definitive standard and that it is most important to be engaging in thinking about these issues and in practice to follow the lead of the client.

Josie also seeks to learn more about various disability perspectives and experiences among Black Americans. Reflecting on her learning, Josie reminds herself that while book learning is important, her client, Regina, will be her best guide in understanding her culture and any other factors that play out in her life. Josie recognizes that in practice, cross-cultural considerations could go unaddressed. She prepares herself for working with Regina by thinking about how she can bring up their different and shared social identities and how she and Regina might be able to build a bridge to co-construct goals, objectives, and an intervention plan for their work together. Another aspect of Josie’s pre-engagement work will involve considering how Regina prefers to refer to her race or ethnicity (as well as other social identities) in written documentation.

Engagement

The engagement phase is a prime opportunity to learn from a client more about their disability culture (if any) and any other cultures the client is affiliated with. This first step is also the time to learn about the client’s experience of disability and other oppressions as well as privileges (Danso, 2015). While doing this work, social workers will utilize the knowledge they have gained during pre-engagement, while simultaneously acknowledging the potential limitations of that knowledge. Central to anti-oppressive practice is the idea that social workers must see disabled people not only as clients, but partners who are also as allies, advocates, and activists who can teach us about their cultures and realities (Baines, 2017). Also important is the ability to add to that knowledge by centering the personal expertise of clients on their life, while being open to learning from others. This is an evolving and shifting process.

Regardless of the social worker’s own disability identity, a key part of the engagement process in practice with disabled people is understanding how disability identity does—or does not—fit into their worldview and self-concept. Just because a person has a disability, it does not mean that their disability is the reason they are seeking services. Instead, consider disability as a social identity in an intersectional approach to engagement. This engagement work could include gathering knowledge from the client about how they prefer to refer to themselves, how they prefer to communicate, and how they learn best – on top of identifying their primary concerns and presenting problems. In discussions of how anti-oppressive practice works, social workers have acknowledged that language is a force in political struggles – especially when it comes to disabled people (Baines, 2017).

Example

As she is about to meet Regina, social worker Josie grounds herself and reflects on the pre-engagement work she did. Josie turned to literature authored by Black American women who have shared their experiences with disability and mental health services. Other readings focused on learning more about autism, rural communities, and related topics, but ultimately she will look to Regina as the expert in her own life, from whom she can learn.

Josie and Regina meet virtually on video via a telehealth platform. Josie begins by introducing herself, explaining confidentiality and agency policies related to their work together, including their current need to meet remotely due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Josie aims to ‘start where the client is’ and asks Regina to share more about herself, beyond what is in the case file. Josie also asks Regina what she would like to work on. Josie thoughtfully moves into a conversation about what it might be like for Regina to be working with someone with different social identities than herself. Josie mentions that she recognizes that there might be things that a White, suburban woman who is not disabled might not understand or know to focus on, but that she is open to being pointed in the right direction. Josie’s action is demonstrative of a power-sharing approach that attempts to narrow the potentially hierarchical gap between social worker and client. Regina explains that she identifies as a Black woman who has more recently embraced her own disability. Regina tells Josie that she is very involved in the Autistic Self Advocacy Network (ASAN), and Josie makes a note to learn more about this organization in order to understand Regina’s worldview better. She asks Regina to talk about how various parts of her identity (e.g., her gender, her race, her disability) interact and influence her life experiences. For example, she asks about Regina’s experience as a female with autism given that the dominant narrative of the autistic experience appears to be male. By directly bringing up these topics, Josie is working to be transparent about working towards creating a positive relationship with Regina, one in which she will feel supported. As the engagement process goes on beyond the first meeting, Josie is sure to demonstrate what she has learned from Regina in her second, third, and fourth meetings—and beyond—by taking a culturally responsive approach that ideally helps Regina to feel heard and seen, such as sharing what she has learned from reading about the ASAN.

Josie recognizes that it is also important to honor and implement the three theoretical frameworks that guide this model of social work practice with the disability community in her documentation work as well as other aspects of client-centered practice. This includes utilizing a critical cultural competence lens in thinking about how she writes about Regina in her case notes-for example, considering how she will document in a way that respects how Regina wants to be referred to (e.g., capitalizing Black) while meeting agency or professional documentation requirements.

Assessment

As the assessment step launches, social workers should be drawing on the critical skills discussed as part of critical cultural competence as well as the reflective and reflexive skills associated with anti-oppressive practice. Considerations of intersectionality in client assessment dovetail with both approaches. Recall that intersectionality is a tool for contextual analysis and action in the form of assessing in the practice of social work (Cho et al., 2013; Collins & Bilge, 2016; Crenshaw, 1995). This framework posits that “people simultaneously occupy multiple positions (positionalities within the socio-political and structural fabric of society” (Ortega & Faller, 2011, p. 31). Using this lens, we consider how potential inequities that clients experience are not caused or maintained by a single factor alone (such as racism, sexism, ableism). Instead, inequities may be created and may continue due to the interactions between multiple manifestations of privilege and oppression. Systems of advantage based on social identities are enacted and enforced internally (within individual people), interpersonally (between individuals and groups), institutionally (within organizations), and structurally (among institutions, across society) (Lawrence & Keleher, 2004). These separate systems work together to organize and justify both privilege and oppression (Collins & Bilge, 2016; Connor, 2006).

A social worker’s embrace of an intersectional framework with the skills of anti-oppressive practice and critical cultural competence includes a focus on a social worker’s actions toward enacting key aspects of critical awareness and knowledge during cross-cultural interactions with clients and their identified circles of support. This process includes the need for social workers to create space during assessment meetings to negotiate and establish disability culture-specific meanings related to presenting problems and modes of operation. Recognizing any intersectionalities and social constructions of disability identity as well as other intersecting identities should be central to this negotiation. This process of negotiation will help social workers determine a culturally appropriate approach to practice and care planning that centers the client’s narrative of their strengths and needs (Almutairi et al., 2015). In addition to the interpersonal aspects of the engagement step, social workers must also work to recognize the social construction of policy and institutional norms that are related to disability or the disability community.

Centering the client’s narrative in the assessment phase can also include embracing the disability rights concept of “nothing about us without us” in co-deciding what presenting problems are—and are not! Another way this has been conceptualized is “about us, by us,” according to the late Massachusetts-based disability rights advocate John Winske (Disability Policy Consortium, 2020). This links to the aspect of critical cultural competence referred to as critical empowerment. Critical empowerment goes beyond the social worker’s recognition of cultural differences, thinking about how the perception of power imbalance functions in the client’s social, historical, and political contexts (Almutairi et al., 2015). For example, a social worker could share their assessment of the client with the client in order to obtain feedback and allow the client to have some agency in how presenting challenges are categorized and framed. In situations where the social worker is present due to legal sanctions, the picture is muddied and requires even more of an attempt to offset the power relations inherent in that situation.

Social workers also need to focus on identifying areas where they can respect the dignity of risk, or the right of disabled people to be able to learn and grow from access to everyday risk. As goals and objectives are being identified by the social worker and client, the social worker should assess for areas in which they might be able to allow clients the dignity of risk. For example, a young mother with an intellectual disability is noted by social workers and nurses in the hospital to forget to feed her new baby. Upon further exploration, the social worker learns that the young woman can read digital but not analog clocks. Replacing the clock in the hospital room and obtaining a digital watch allow the mother to have an opportunity to meet her baby’s needs appropriately. In this scenario, the dignity of risk is allowed for in a safety net context.

Example

In her first meeting with Regina, Josie was very focused on building rapport in a culturally responsive manner, but she was also beginning to make observations about Regina as part of her assessment process. As Josie uses the agency-mandated clinical assessment tools in her work with Regina, she is mindful of whether or not these tools utilize a culturally-sensitive or culturally-specific lens. She makes sure to integrate critical perspectives with the information gained from the clinical assessment tools. As such, Josie may use additional tools to support collaborative reflection on Regina’s experiences (see, for example, this privilege and oppression matrix). Josie also reflects on the differences between meeting clients virtually on video compared to in-home sessions as it relates to the application of anti-oppressive practice techniques, for example.

In order to create a disability-positive process, Josie thinks about the “nothing about us without us” credo that many disability rights advocates call for (something she has learned about on the ASAN website) and uses it to inspire her approach to assessment. This translates into Josie asking Regina to step outside of herself to describe the person and situation she sees, using her own words to describe both strengths and challenges. She also asks Regina to dialogue with her friends in the ASAN chat room about the challenges she is facing, in order to help Regina build community and develop new perspectives. Using Regina’s language for conceptualizing a presenting problem can be an empowering action. For example, Regina describes how her colleagues have a hard time with her “tics.” Exploring further, Josie learns that the comment refers to incidents in which Regina is compelled to touch or push someone if they have accidentally bumped into her. This has led to conflict. Josie can also look back to the conversation she had with Regina about their differing social identities in order to ask Regina to reflect on how her social location may impact or inform her presenting problem/s. Regina says that as a Black woman, she sometimes feels marginalized in ways her autistic friends who are White “just don’t get.” Josie and Regina discuss how the experiences of people within a group can differ due to the interactions between multiple manifestations of privilege and oppression in their lives. The goal of this line of conversation is to co-create a narrative assessment related to the presenting problem/s and plans for work together that include an understanding of both the personal and systemic issues at play.

Intervention

Once the social worker and client have co-constructed goals and objectives, a care plan can be developed and the social work interventions can commence in partnership with the client (Baines, 2017). Ideally, the social worker’s anti-oppressive intervention should not only focus on integrating the disabled person into society but also address ways that society, in micro form, can be changed (Baines, 2017). These interventions will foster community inclusion, a key disability rights concept focused on access to the community for disabled people. Additionally, self-determination on the part of the client will be respected while inclusion of circles of support will be promoted where appropriate.

Example

Once Regina and Josie have co-constructed both an assessment as well as goals and objectives for their ongoing video work together (a.k.a. “the intervention”), the nature of the work is chosen, and the work process commences. Ideally, this process will include a conversation about how the pair will know when services are no longer needed (in order to facilitate termination, later). As Regina has had a choice in how the intervention is structured, this conversation will support her engagement with the process. In her work with Regina, Josie will be sure to weave in intervention approaches that recognize both Regina’s desire to more fully integrate into work and family environments in any needed ways and address micro-options for how these environments can be more inclusive for Regina and other disabled people.

Josie approaches her work from multiple fronts. First, she conducts different reality-based role plays with Regina to practice noticing social cues, which will help with Regina’s inclusion in her workplace community. Second, regarding the need for structural change, as Regina and Josie work together, Regina feels increasingly more comfortable advocating for herself to her manager around neurodiversity acceptance. At Regina’s request, the manager encourages the workplace’s diversity committee to take on the challenge of learning more about neurodiversity and exploring the structures in the workplace that may or may not promote inclusion. This includes recognition of the larger issue of greater potential for law enforcement involvement in situations involving Black disabled people – something that Regina could be at risk of during one of her pushing incidents at work (McCauley, 2017; Thompson, 2021).

Third, Josie also works with Regina’s family via the telehealth health platform to identify opportunities to do things differently, in ways that make sense to how Regina likes to operate, in order to address a small way that the family culture can be changed. This might mean, for example, building in a daily time for Regina to share new information about her passion area with her family – endangered species of mammals across the world. Having this time allows Regina to talk about topics she is passionate about with the people she loves, but also do so in a way that does not overwhelm the family, by limiting discussion of the topic to once per day versus experiencing it as a constant topic of conversation. In doing this, Josie is aware of how shared familial and cultural norms intersect with personal identities and experiences and need to be addressed all together using an intersectional perspective. The technical challenges involved in conducting family counseling via video with Regina’s family during this time have been particularly difficult, but Josie has used similar strategies of checking in with the family during the telehealth sessions as she uses with Regina.

At various points during their work together, Regina and Josie move their individual sessions onto the telephone due to challenges related to Internet access for the video telehealth platform. This presents a challenge for some of the role-playing that the duo are working on together given the need for Regina to develop skills in the area of identifying visual cues in interpersonal interactions. Josie works to check in with Regina on video and/or telephone to make sure that their process is a fit for Regina’s needs. Questions she may ask include: “How are the role plays going for you?” “What are you gaining from these role plays towards your therapeutic goals?” “Is there anything we should change in how we are doing this work together?” This also involves Josie needing to attend to and respond to subtle cues that Regina may share in their interactions virtually or on the telephone.

Termination

During the termination step of practice, it is vital to recognize power dynamics and imbalances especially as they relate to structural issues of privilege and oppression as well as the social worker’s role authority and the client’s vulnerability (Baines, 2017). For example, issues of power dynamics can arise during termination regarding decisions about when and how services and relationships are terminated – especially when the services/relationships are involuntary. Even if mandated involvement is not the case, honoring the client’s dignity of risk will be a central concern for an anti-oppressive social work practitioner. Ideally, the co-constructed intervention will have led to changes in the client’s life allowing for them to resume life without the support of a social worker and, therefore, allowing for the dignity of risk.

Example

Regina voluntarily sought out assistance from Josie’s outpatient mental health center in order to address her challenges at work and at home. Over time, Regina came to really enjoy her weekly virtual counseling sessions with Josie, even though the work was hard and they sometimes experienced technical difficulties. Josie became an important part of her life. Josie has started to notice that Regina’s work life has begun to stabilize, as has her family life. Regina has been able to learn more about how to notice social cues and respond to them appropriately in a way that fosters her community inclusion. She has also started to do a better job of managing her tics in a way that promotes the potential for continued community inclusion. Finally, Regina has developed a greater sense of empowerment related to advocating with her family and employer regarding disability and inclusion.

Using an anti-oppressive practice lens, Josie recognizes that her role as a social worker comes with a certain authority. She reminds herself of Regina’s potential vulnerability around the termination of services, given the positive relationship and even potential dependency that has developed. It is important, though, to acknowledge dignity of risk in clients moving on independently with their lives without the support of a therapeutic presence.

Reminding Regina of their conversation about when they thought services would no longer be needed, Josie brings up the topic of termination. As there has been a precursor to this conversation, Regina is more prepared to think about termination than she might have been. Regina agrees that her presenting problems have been well addressed and that she understands the need for termination, but asks to be able to contact Josie for support once in a while if she needs it. Given that Josie’s agency allows for this via a specialized aftercare program, she agrees to periodic check-ins, acknowledging that this could be preventative in addressing any challenges Regina may encounter in the future.

Evaluation

At the assessment stage, the social worker and client co-constructed goals and objectives as well as identified measures of progress or success. These goals and objectives feed directly into how the evaluation step should be accomplished. At the evaluation step, which should be continuous throughout the planned change process, client-approved measures of progress or success should be considered carefully, centering the client’s narrative of their experience during the intervention process. This reflection may result in the use of explicit evaluation techniques that are qualitative in nature as opposed to the use of quantitative data collection instruments that may not be culturally appropriate across a range of social identity categories (Danso, 2015). Even with qualitative inquiry as part of the explicit evaluation process, power differentials should be noticed and balanced in the interview setup (Rubin & Babbie, 2014). For example, Danso (2015) writes “Interview practices that align with the community’s cultural norms could reduce power differentials in the interview process. Interviews should be conducted in ways that acknowledge and respect personal and cultural idiosyncrasies. Using cultural concepts and expressions or inviting participants to suggest ways for conducting interviews within the community would enable participants to feel validated regarding their culture or self-esteem” (p. 581). These considerations extend to the data analysis and data reporting process as well (Danso, 2015).

Consideration of implicit as well as explicit evaluation data should be engaged in – especially with respect to how clients view their experience with the intervention (Danso, 2015). Implicit evaluation is focused on informal discussions and informal observations. Going back to considerations of intersectionality are equally important at this step. Intersectionality as a framework encourages practitioners to move beyond viewing and responding to social inequities through a disability-only or a race-only lens and causes people to understand and respond to these inequities at once (Collins & Bilge, 2016). As there is no singular way to be a person of color or to be a person with a disability, service systems must be envisioned and built with inclusive equity in mind. Intersectionality is an essential conceptual tool as it offers insight into the interactions between various social identities and society, while also offering an opportunity to evaluate, namely, assess, modify, and build services that will reduce or eradicate intersectional inequities. Using an intersectional frame is a form of social action at the evaluation step.

Example

As Josie begins the process of termination, she reflects that the termination and evaluation phases are closely intertwined. Using an anti-oppressive practice approach, she and Regina began their work by identifying measures of progress or success for use in the continuous evaluation of the intervention process. By touching on these measures during each session through the use of electronic tracking tools, Josie can help Regina document her process on what brought her to seek help. This creates a visual map for Regina to look at and respond to. This also helps Josie to meet the National Association of Social Workers’ Code of Ethics (2017) requirement to evaluate all practice. This evaluation interaction lays a foundation both for feedback about how the process of treatment is going – and also for having a conversation about termination when the time is right (based on the outcome data!). This type of data-driven evaluation is known as explicit evaluation. Josie also leads Regina in intersectionality-informed discussions that may be thought of as implicit evaluations, related to how, in the end, Regina feels her intersecting social identities may have played into the intervention process and her approach to addressing her challenges.

Comparison of the Model for Social Work Practice with Disability Communities to Existing Disability Community-Focused Practice Models

Two disability practice-related frameworks have been identified in the United States context: the independent living model and the disability competent care model. The independent living model (ILM) is very similar to the social model of disability. The ILM conceptualizes disability as a social construct located in society (i.e., the social model of disability) versus being located in an individual body part (a.k.a. the medical model of disability) (Oliver et al., 2012). The focus of the ILM is advocating for independence for disabled people with the acknowledgement that they are their own experts about what they need and which services are ideal to meet those needs (National Center for Independent Living, 2020). Thought of as driven by ‘consumer control,’ many believe the ILM was initiated by disability civil rights legend Ed Roberts and his group of ‘Rolling Quads’ at the University of California at Berkeley, often thought of as the birthplace of the disability civil rights movement and the independent living movement (McCrary, 2017).

In addition to being heavily influenced by the civil rights movement of the 1960s and 1970s, the ILM was also jump-started by the process of deinstitutionalization. During this time period, people with significant disabilities began to have some opportunities to live in community-based settings as opposed to nursing homes and other institutional settings—although quasi-institutional settings such as group homes and other shared living arrangements sprung up at this time as well. These factors caused disability civil rights advocates to speak out for equal opportunity in figuring out how to live, work, and participate in the community, all of which had major implications for independent living potential. The ILM resulted in the development of many independent living centers nationwide (Oliver et al., 2012).

The shift from institutional to independent living was not coupled with sufficient funding for supporting disabled people in the community (Dunn & Langdon, 2016; Larson, 2016). This lack of funding continues to date, with contemporary social welfare programs often being linked to a person’s ability to obtain paid work (Duffy & Elder-Woodward, 2019). However, disabled persons commonly experience ableism and inaccessibility when seeking work or when already employed, and often have additional expenses increasing their costs of living (Saffer, Nolte, & Duffy, 2018). Until these barriers are addressed or removed, sufficient and specific disability support benefits are needed not only to reduce the poverty levels of disabled people but to ensure a more than adequate standard of living (Saffer et al., 2018).

For social workers practicing under the ILM model, such as those in independent living centers, it is important to resist professionalizing the work “on the basis of an expertise in impairment as a cause of social need” as this would be an oppressive act (Oliver et al., 2012, p. 152; Hiranandani, 2005). Rather, social workers need to commit to the removal of barriers causing disability—in an equal partnership with disabled people. Specifically, “the problems of disabled people, or social workers, are not resolved by the incorporation of empowerment as an instrumental competence” (Oliver et al., 2012, p. 152).

The model for social work practice with the disability community presented above aligns with the ILM model of practice in how it addresses both the personal and social aspects of living with a disability and the need for social workers to defer to the client as an expert on their own needs.

The disability competent care model (DCC) was developed by The Lewin Group in conjunction with disabled people and service system consultants and adopted by the Council on Social Work Education (CSWE) as a guiding framework for practice (Disability Competent Care Working Group, CSWE, 2019). This DCC model is noted to take a person-centered approach to providing social work that is focused on supporting people with functional limitations in achieving best-possible functionality. This process is conceptualized as including work with an interdisciplinary care group that views and supports clients as unique people versus just a diagnosis or condition per the medical model of disability. In addition to responding to a client’s physical and clinical needs, DCC also takes into consideration their social, emotional, intellectual, and spiritual needs. Further, this model supports both self-determination and community inclusion with a focus on providing supports and services that allow for home-based self-sufficiency. There are seven pillars which, taken together, comprise the concept of DCC. These pillars include understanding the DCC model, participant engagement, access, primary care, care coordination, long-term supports, and behavioral health. For more information about this model, see Resources for Integrated Care.

In discussing the DCC, the CSWE calls for “moving away from a medical model of disability perspective to a constructionist or social model approach” (p. 7). However, it does not seem that the DCC model focuses on addressing or removing the barriers experienced by disabled persons and communities (Oliver et al., 2012). The DCC model may also be critiqued for not having an explicit inclusion of disability culture. In her work on disability culture and cultural competency in social work, Marilyn Dupré (2012) writes that social workers need to move beyond an assumption of the possibility of cultural competence, to an embrace of learning about disability culture. The model for social work practice with the disability community builds on the utilitarian DCC model by layering on steps for practice infused with considerations stemming from intersectionality, critical cultural competence, and anti-oppressive practice.

Conclusion

Keeping in mind the model for social work practice with the disability community as you approach your work with disabled people, think about the ways you can infuse your practice with the theoretical perspectives of critical cultural competence, intersectionality, anti-oppressive practice, and the tenets of disability-positive practice: the dignity of risk; self-determination; circles of support; community inclusion; and the ‘nothing about us without us’ credo. Consider your own personal and social identities, experiences of privilege and oppression, and ways you can be reflexive and reflective in approaching your practice with disabled clients.

References

Almutairi, A., Dahinten, V., & Rodney, P. (2015). Almutairi’s critical cultural competence model for a multicultural healthcare environment. Nursing Inquiry, 22(4), 317-325.

Appiah, K. (2020, June 18). The case for capitalizing the B in Black. The Atlantic. https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2020/06/time-to-capitalize-blackand-white/613159/

Baines, D. (2007). Anti-oppressive social work practice: Fighting for space, fighting for change. In D. Baines (Ed.), Doing anti-oppressive practice: Building transformative politicized social work (pp. 1-30). Fernwood Publishing.

Baines, D. (2011). An overview of anti-oppressive practice: Roots, theory, tensions. In D. Baines (Ed.), Doing anti-oppressive practice: Social justice social work (2nd ed., pp. 2-24). Fernwood Publishing.

Baines, D. (2017). An overview of anti-oppressive practice: Roots, theory, tensions. In D. Baines (Ed.), Doing anti-oppressive practice: Social justice social work (3rd ed., pp. 2-29). Canadian Scholars’ Press.

Baskin, C. (2016). Strong Helpers’ Teachings: The value of Indigenous knowledges in the helping professions (2nd ed.). Canadian Scholars’ Press.

Brown, C. G. (2012). Anti-oppression through a postmodern lens: Dismantling the master’s conceptual tools in discursive social work practice. Critical Social Work, 13(1), 34-65.

Bubar, R., Cespedes, K., & Bundy-Fazioli, K. (2016). Intersectionality and social work: Omissions of race, class, and sexuality in graduate school education. Journal of Social Work Education, 52(3), 283-296.

Campbell, C. (2003). Anti-oppressive theory and practice as the organizing theme for social work education: The case in favor. Canadian Social Work Review, 20(1), 121-126.

Carter, I., Hanes, R., & MacDonald, J. (2012). The inaccessible road not taken: The trials, tribulations and successes of disability inclusion within social work post-secondary education. Canadian Disability Studies Journal, 1(1), 109-142.

Carter, I., Hanes, R., & MacDonald, J. (2017). Beyond the social model of disability: Engaging in anti-oppressive social work practice. In D. Baines (Ed.), Doing anti-oppressive practice: Social justice social work (3rd ed., pp. 153-171). Canadian Scholars’ Press.

Casado, B., Negi, J., & Hong, M. (2012). Culturally competent social work research: Methodological considerations for research with language minorities. Social Work, 57(1), 1-10.

Cho, S., Crenshaw, K. W., & McCall, L. (2013). Toward a field of intersectionality studies: Theory, applications, and praxis. Signs, 38(4), 785-810.

Collins, P. H. (1990). Black Feminist thought: Knowledge, consciousness, and the politics of empowerment. Unwin Hyman.

Collins, P. H. (2000). Black Feminist thought: Knowledge, consciousness, and the politics of empowerment (2nd ed.). Routledge.

Collins, P. H. (2015). Intersectionality’s definitional dilemmas. Annual Review of Sociology, 41(1), 1-20.

Collins, P. H., & Bilge, S. (2016). Intersectionality. Polity Press.

Collins, P. H. (2019). Intersectionality as critical social theory. Duke University Press.

Connor, D. (2006). Michael’s story: “I get into so much trouble just by walking”: Narrative knowing and life at the intersections of learning disability, race, and class. Equity and Excellence in Education, 39, 154-165.

Cox, L. E., Tice, C. J., & Long, D. D. (2019). History of social work . In Introduction to social work: An advocacy-based profession (2nd ed., pp. 23-37). SAGE Publications.

Crenshaw, K. (1989). Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A Black Feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory and antiracist politics. University of Chicago Legal Forum, 1(8), 139-167.

Crenshaw, K. (1991). Mapping the margins: Intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color. Stanford Law Review, 43(6), 1241-1299.

Crenshaw, K. (1995). Mapping the margins: Intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color. In K. Crenshaw, N. Gotanda, G. Peller, & K. Thomas (Eds.), Critical Race Theory: The key writings that formed the movement. The New Press.

Cross, T. L., Bazron, B. J., Dennis, K. W., & Isaacs, M. R. (1989). Towards a culturally system of care: A monograph on effective services for minority children who are severely emotionally disturbed (Vol. 1). CASSP Technical Assistance Center, Georgetown University Child Development Center. https://archive.org/details/towardsculturall00un

Dalrymple, J., & Burke, B. (1995). Anti-oppressive practice, social care and the law. Open University Press.

Dalrymple, J., & Burke, B. (2006). Anti-oppressive practice, social care and the law (2nd ed.). Open University Press.

Danso, R. (2015). An integrated framework of critical cultural competence and anti-oppressive practice for social justice social work research. Qualitative Social Work, 14(4), 572-588.

Danso, R. (2018). Cultural competence and cultural humility: A critical reflection on key cultural diversity concepts. Journal of Social Work, 18(4), 410-430.

DeRoos, Y. S. (1990). The development of practice wisdom through human problem-solving processes. Social Service Review, 64, 276-287.

Disability Competent Care Working Group, Council on Social Work Education Council on Disability and Persons with Disabilities, (2019). Curricular resource on disability and disability-competent care: Diversity and justice supplement. https://cswe.org/Centers-Initiatives/Centers/Center-for-Diversity/Curricular-Resource-on-Issues-of-Disability-and-Di.aspx

Disability Policy Consortium. (2020). About us, by us. https://www.dpcma.org/dpc-publication-about-us-by-us

Drywater-Whitekiller, V. (2014) Family group conferencing: An Indigenous practice approach to compliance with the Indian Child Welfare Act. Journal of Public Child Welfare, 8(3), 260-278.

Dominelli, L. (2002). Anti-oppressive social work theory and practice. Palgrave Macmillan.