5

Sharyn DeZelar and Olivia Elick

Learning Objectives:

- To explain how educational services for disabled children are organized in the United States

- To learn about key education-related policies relevant to disabled people in the U.S.

- To explain the process of transitioning from the educational system to adult disability service systems

This chapter will discuss access to education from early childhood, to adolescence and through university. At the earlier end of the age spectrum, we will focus on how disabled children access appropriate educational services. We will also discuss how general education and special education settings do and do not support disabled children, with a focus on the experience of disability stigma and mainstreaming practices. We will provide a discussion of the overrepresentation of disabled students of color in suspension and expulsion cases in elementary, middle and high school settings. The use of residential treatment centers will be addressed, including a discussion of the controversial use of shock/aversive therapy in some settings. A particular focus of this chapter will be the discussion of the often-fraught process of transition from youth service systems to adult service systems. Considerations about the inaccessibility of higher education institutions will also be presented. We will review key education-related laws, policies and programs relevant to disabled people in the U.S. For example, we will discuss the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act which provides a pathway to personalized, accessible services for youth. Additionally, we discuss the Chafee Foster Care Program for Successful Transition to Adulthood (42 U.S. Code § 677) which offers support to foster children, one-third of whom have disabilities.

Introduction

With over 3 million children and youth under the age of 18 in the U.S. recognized as having a disability (Young & Crankshaw, 2021), one of the main avenues for receiving supports and services for children, youth and their families is through the U.S. public education system. With the enactment of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act of 1990 (IDEA), all children are entitled to a Free Appropriate Public Education (FAPE, 1975), which serves as a human rights act for disabled children and youth, and their families. Disability services offered through the U.S. public education system are provided regardless of health insurance status, ability to pay or documentation of legal status in the U.S., and free transportation is provided. Therefore, this is one of the most accessible sectors of disability services in the U.S., and all children and youth (either currently disabled or with conditions that have the potential to be disabling) living in the U.S. are entitled to receive the services, such as accommodations, educational supports, and a variety of individualized services and therapies. However, this system is plagued with injustice in several areas, including disproportionate representation of BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, and other People of Color) [1] students in special education services in general and with specific diagnoses, and disciplinary policies (e.g. suspensions and expulsions) and practices that significantly impact students with disabilities with particular intersections with race, ethnicity, gender, and LGBTQ2S (Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer or Questioning, Two-Spirit)[2] status.

History: Disability (In)Justice in Education Policy

Despite the intended accessibility and entitlement of education and services for children and youth within the public education system, historically, access to education has not been a guaranteed right, nor has the school building been a desirable space for everyone to learn. For example, residential boarding schools (a predecessor of the U.S. education system) were created as a tool to enact removal of Native American children from their communities, force assimilation to colonialist ways, and at times, outright elimination of the Indigenous peoples of North America (Keating, 2020), out of colonialist desires for (and sense of entitlement to) Indigenous lands (Child, 2018). For over 100 years, between the mid-1800s and mid-1900s, Indigenous children were “forcibly removed from their homes and put into Christian and government run schools… with the intention to erase Indian culture and identity [through means of] neglect and verbal, physical, and sexual abuse” (Regents of the University of Minnesota, 2016, Slide 3). This violent and oppressive history did not begin with residential boarding schools, rather in the 1500s with the invasion of European colonizers inflicting white settler colonialism, genocide, and long-lasting transatlantic enslavement of African and Indigenous people (Elliott and Hughes, 2019). There are elements throughout this chapter that highlight how the education system has worked to both uphold and dismantle racist and ableist practices and policies throughout history and today.

This is crucial context for this chapter, as it highlights how deeply our state systems (including the education system) were founded on racist, colonialist, and ableist beliefs. Leah Lakshmi Piepna-Samarasinha, in their book Care Work: Dreaming Disability Justice, states that these systems, despite efforts of reform and justice, “will not save us, because [they were] created to kill us” (2018, p.23). There are parallels as well as intersections between systemic racism and ableism due to views of inferiority of both non-white, and non-abled people. Moreover, regarding intersectionality, “associations of race with disability have been used to justify the brutality of slavery, colonialism, and neo-colonialism” throughout history (Erevelles, Minear, 2010, p.132 as cited in Migambi and Neal, 2018, p.3). This oppression was justified through “The Ugly Laws” which spanned from mid-1700’s to 1970, which “stated that many disabled people were ‘too ugly’ to take up space in public” (Lakshmi Piepna-Samarasinha, 2018, p.23) and were identified through “labels as ‘imbeciles’ and ‘idiots’ and used to restrict unwanted immigration through the use of the legal system” (Schwik, 2009 as cited by Migambi and Neal, 2018, p.4). This fueled “mass creation in the 1800’s of hospitals, ‘homes,’ ‘sanitoriums,’ and ‘charitable institutions’ where it was the norm for disabled, sick, mad, and Deaf people to be sequestered from able-bodied ‘normal society” and these institutions “overlapped with other prison/carceral systems” (Lakshmi Piepna-Samarasinha, 2018, p.23). This relates to the foundation of the U.S. education system in many ways, both obvious and subtle.

The public education system was developed in the context of these racist and ableist practices of control and institutionalization in the 19th century. What was then referred to as “common schools and institutions,” shifted education of children from “private and philanthropic efforts” to state and eventually local district school systems (Richardson and Parker, 1993, p. 363-364). The “passage of compulsory school attendance” greatly affected the meaning, legitimacy, and authority of the school and state control (Richardson and Parker, 1993, p. 363-364). The passage of mandatory school attendance greatly affected the meaning, legitimacy, and authority of the school and of state control over education (Richardson and Parker, 1993). This regulation gave schools the discretion of “specifying physical and mental deviations as grounds for exemption” which vicariously gave the state control over who participated in “residential facilities for exceptional children” versus “common school education” (Richardson and Parker, 1993, p. 364). Schools were then required to meet the parameters of the attendance policy, thus created the “ungraded class” which included the “poor, physically unkept and disorderly children,” which was “most common in urban school systems, and later became the special class for exceptional children” (Richardson and Parker, 1993, p.364).

The school system was industrialized in the late 19th century, where the school system acted as an extension of the state quite similar to the codified ways it does today. Richardson and Parker explain that additionally, “youth who were ‘vicious and immoral’ in character or found begging or frequenting immoral places could be excluded from attendance and committed to the state reform or industrial school” (1993, p. 364). This experience was undoubtedly heightened and targeted for BIPOC, LGBTQ2S and disabled individuals which vastly influenced the experience of being criminalized. The state reform and industrial schools were separated and segregated from the “normal” schools, eventually leading to the juvenile justice system, in which children with disabilities were, and still are, significantly overrepresented (Nanda, 2019, p.270). The disability community was seen as the “other, [individuals] to be cured, or if they could not be cured, to be isolated [and] institutionalized” (Chamusco, 2017, p.1288). These interrelationships between individuals and state agencies were “reinforced by practices of eugenics, hygiene, and public health” and embraced specifically within schools where these practices were “administered and politicized as a form of social control” (Petrina, 2006, p.503). Over the last few decades, there has definitely been a monumental shift in access, equity, and safety as it relates to those with disabilities being allowed, included, and accepted into the educational community.

During the Civil Rights Era there was a visible shift from custodialism (the state remains custody of the individual) to integrationism (individual is integrated into the mainstream) of what is considered equality in education (TenBroek & Matson, 1966, as cited by Chamusco, 2017). Skiba states that “special education was borne out of, and owes a debt to, the civil rights movement” and yet it is “highly ironic that racial disparities in rates of special education services remain one of the key indicators of inequity in our nation’s education system” (2008, p. 264). Baglieri et al. (2011) states that a “normative center” has been created in schools, in which White, able, and middle-class bodies are considered the standard, and deviations from this are less desirable in the school system. This brings into question, to what degree is the right to education ensured in the United States? Beatty asserts that “the right to a free public education is not guaranteed by constitutional rights, but has come to fruition from case law and state statutes, such as the well-known Brown v. Board of Education, that ensured the state to provide equal education for all students regardless of ethnicity, but the focus did not emphasize disability rights explicitly” (2013, p.532). The guarantee of education is founded on assimilation and social control, and is entrenched in equating success with what is considered white-normative behavior (Migambi & Neal, 2018). This exemplifies the intersectionality of race/ethnicity and disability, and also the continuation of white supremacy and colonization within our classrooms.

Educational Policy Overview

The following summary provides an overview of the development of educational policy in the U.S. as it relates to providing access to education and services for disabled children and youth. It does not delve into the intricacies of the disparities in representation of BIPOC students in special education, nor the magnitude of injustice as it relates to discipline policies, expulsion and suspension rates, and a number of other policies and procedures. Additional discussion of some of these issues and practices will be covered later in the chapter, and resources and links to further information on these injustices will be provided. A deeper dive into some of these policies is provided in Chapter 3: Major Disability Policies. The focus in this section is on educational access and practices.

Policy: Section 504 of Rehabilitation Act of 1973

Section 504 of The Rehabilitation Act of 1973 is the first civil rights law pertaining to disabilities in the U.S., and has been influential in antidiscrimination policies in employment, education, and the definition of disability. It plays a crucial part in the disability justice policy landscape, and informed the creation of the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990. Enacted during the disability civil rights movement, the policy prohibits discrimination based on disability or health condition by any programs that receive federal funding. Section 504 considers a person with a disability to have a condition, either physical, mental, emotional that interrupts a “major life activity,” record of such an impairment, or being “regarded as” having an impairment (U.S. Department of Education, 2020). This definition is broader than the one considered for services under IDEA (which is a categorical, medical model) which improves access to services within the education system for some students, however often requires advocacy from the individual or family, often at a point of discrimination or inaccessibility, even though the precedent has been set as standard. Section has 504 reached a wide array of settings to decrease and eliminate discrimination towards persons with disabilities.

Link to policy (Sections, Amendments, etc.): https://www.eeoc.gov/rehabilitation-act-1973-original-text

Policy: Education for All Handicapped Children Act of 1975

The Education for All Handicapped Children Act of 1975 (EAHCA) was the predecessor to the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act of 1990. This federal law required public schools to provide appropriate education services to disabled children aged 3 to 21 years old. This early version of the current educational act was extremely monumental in ensuring access to education for those with disabilities. EAHCA was a larger catalyst than the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, in supporting young people and their rights to equal and free education regardless of disability status. Prior to the enactment of the EAHCA, it was common practice for children to be denied access to public education. According to the U.S. Department of Education, “in 1970, U.S. schools educated only one in five children with disabilities, and many states had laws outright excluding certain students, including children who were deaf, blind, emotionally disturbed, or had an intellectual disability” (2020). These exclusionary practices were inequitable and disturbingly legal. The EAHCA was considered radical and vastly transformative as it was now federal law that “all children with disabilities have a Free Appropriate Public Education that emphasizes special education and related services designed to meet their needs” (U.S. Department of Education, 2020).

Link to Policy (Sections, Amendments, etc.): https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/STATUTE-89/pdf/STATUTE-89-Pg773.pdf

Policy: Individuals with Disabilities Education Act of 1990

The Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) was renamed in 1990 from the former Education for All Handicapped Children Act of 1975, with some revamping that enforced more accountability for a Free Appropriate Public Education (FAPE), and stronger mandates and accountability for federal funding. Mandates for services were added for children from birth through age two. Additionally, the individualized family service plan (IFSP) and the individualized education plan (IEP) were established as requirements. Subsequent reauthorizations and amendments have occurred in 1997, 2004, and 2008. Box 5.1 provides a summary of the key components of IDEA.

Box 5.1

Summary of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA)

- Part A, General Provisions: Lays the foundation for the rest of the act. Creates the Office of Special Education Programs. Defines terms

- Part B, Assistance for Education of All Children with Disabilities: Provides educational guidelines for children ages 3 to 21. States are required to provide education for disabled students. Dictates financial support for districts. Some of the key principles and benefits for disabled children include:

- Free appropriate public education (FAPE)

- Identification and evaluation

- Individualized education plans (IEP)

- Least restrictive environment

- Due process safeguards

- Parent/student participation and shared decision making

- Part C, Infants and Toddlers with Disabilities: Provides educational guidelines for services for children ages birth through age 2. States are required to provide services for children and families. Some of the key principles and benefits for disabled children and their families include:

- Expansion of requirements for a statewide system, serving young children

- Individualized family service plans (IFSP)

- Part D, National Activities to Improve Education of Children with Disabilities: Describes national activities aimed at improving the lives of children with disabilities as a whole. Includes grants for improvement and transitional activities.

There was an urgent need for the reforms under IDEA, as the history of many individuals with disabilities included “state institutions with restrictive settings with minimal food, clothing, and shelter, and persons with disabilities were often merely accommodated rather than assessed, educated, and rehabilitated” (U.S. Department of Education, 2020). Turnbull posits that IDEA can be categorized as a school reform law, civil rights law, and welfare state reform law, as the breadth of this bill expands across school policy, family involvement, and larger systemic practices (2005).

This policy dramatically transformed the system of special education and disability services as it relates to education, and has positioned the school as a setting of referral for inhouse services as well as state services for individuals with disabilities and their families. The most monumental aspect of the revamping of Education for All Handicapped Children into IDEA is that a young person with a disability cannot be turned away from an education, solely based on their disability. This act ensured that students have guarantee to an individualized education led by the students’ needs and with familial involvement in decision making.

Eligibility criteria. There is difference in the definition of disability across IDEA versus Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act and the Americans with Disabilities Act, which has been controversial. While Section 504 eligibility more simply requires a condition (based on school or health care provider evaluation) that limits a major life activity, the IDEA requirements are categorical in the diagnosis, and this diagnosis must negatively impact learning. Children must meet these two criteria (again, based on school evaluation) in order to be eligible for services under IDEA:

- Diagnostic category: 1. Intellectual Disability; 2. Hearing impairment; 3. Visual Impairment; 4. Speech or Language impairment; 5. Emotional disturbance; 6. Orthopedic impairment; 7. Other health impairment; 8. Traumatic brain injury; 9. Deaf-blindness; 10. Specific Learning Disability; 11. Autism; 12. Developmental delay; or 13. Multiple Disabilities. For definitions of these disability categories, please see: https://sites.ed.gov/idea/regs/b/a/300.8

- Has a need for special education and related services (IDEA, 2020).

This stricter and medical definition of disability under IDEA results in some children not being eligible for services, despite their need. The interaction of Section 504 and ADA protections also adds additional layers, definitions, and implementations. These protections vary from state to state, and case by case, which simultaneously creates broader implementation for some students, while also creating disparities and individual discretion of those most often in positions of power. One benefit of the process established for determining the diagnostic category for services under IDEA is the ability for schools to give diagnoses for service eligibility without use of the medical community outside of the school setting. This removes barriers for families in accessing traditional medical services, including avoiding long waiting lists and lack of insurance. This is commonly referred to as a “school diagnosis” versus a medical diagnosis. The services received under both policies of 504 and IDEA are explored more thoroughly in the section titled “Providing Services for School-Aged Children and Youth” later in this chapter.

Link to Policy (Sections, Amendments, etc.): https://uscode.house.gov/view.xhtml?path=/prelim@title20/chapter33&edition=prelim

Concept Check. Explore the following brief video from YourSpecialEducationRights.com that clarifies the differences between 504 and IDEA, including eligibility differences: IDEA Basics: (504 Plan) How is an IEP Different from a 504 Plan?

Policy: No Child Left Behind, 2001/2002

No Child Left Behind (NCLB) is a controversial policy that has resulted in polarized outcomes for both students and education funding across the nation. The stated intention was to create more assessment measures of effective education and decrease the achievement gap (the disparity between those deemed “successful” and meeting basic standards in school and those not meeting that standard), however it used a coercive strategy of further industrializing education through widespread standardized testing and creating higher and often unattainable standards that resulted in punitive measures for schools, which resulted in further increasing the achievement gap. There were plenty of pitfalls through this legislation that impacted the level of funding, turn over, eventual closure, and functionality of schools for all students, and especially those with disabilities. Lanear and Frattura identify these pitfalls as:

- Segregating groups of students to remediate for purposes of increased test score performance

- Blaming disadvantaged students for low test scores, creating culture of those ‘wanted vs. unwanted’

- Testing proficiency vs. pedagogy of passion, awareness, learning, new knowledge, application, and evaluation

- Assuming teachers are the source of the achievement gap instead of systemic inequity

- Practice of content-based curriculum instead of application of information

- Measuring success by test scores does not serve different levels of disability/language skills in comprehension and acquired knowledge

- Measuring about grade level as proficiency instead of independence and autonomy

- A brief timeframe in which students are required to achieve proficiency (2007, p. 103).

The tension between the rights given within IDEA and the pressures of NCLB was not conducive to ensuring equitable education to students with disabilities. Unfortunately, the negative implications for a school deemed “failing” by the standardized testing measures of NCLB became a priority to avoid, thus resulting in a conflict between the “one size fits all philosophy” of NCLB, and the “highly individualized” programming under IDEA in meeting the needs of students with disabilities (Moores, 2011, p.525).

Link to Policy (Sections, Amendments, etc.): https://www.congress.gov/bill/107th-congress/house-bill/1

Policy: Every Student Succeeds Act, 2015

The Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) replaced No Child Left Behind in 2015, reauthorizing the Elementary and Secondary Education Act, which is committed to educational equity throughout the nation (ESSA, 2020). The provisions proposed within the ESSA include “upholding critical protections for disadvantaged/high-need students, a first-time requirement that all students be taught to high academic standards in efforts for college/career readiness, an assurance that information is provided to the whole community regarding annual statewide assessments that measure students’ progress, help supporting and growing local innovations, sustaining and expanding administrations’ historic investment in high-quality preschool programs, maintaining the expectation of accountability and action to effect positive change in our lowest-performing schools” (ESSA, 2020, https://www.ed.gov/essa?src=ft ). This broad terminology intends to uphold accountability without punitive measures but give states more control of their own school systems.

Link to Policy (Sections, Amendments, etc.) – https://www.ed.gov/essa

Services for Disabled Children and Youth in the Education System

As previously reviewed, the major policy that dictates disability service provision in the education system today is the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) of 1990, with the most recent reauthorization in 2008. Additional students are covered under section 504. The following section will provide an overview of the prevalence of IDEA and 504 usage, disparities in service usage, and further descriptions of services provided in school settings for children ages birth through 21 in the programs of Early Childhood Special Education, services for school-aged children, and Transitions programming. Access to programming at the University level will also be discussed.

Prevalence

Birth to Three

Services for children ages birth to three with (or at risk of developing) disabilities receive services under Part C of IDEA, via partnership with local organizations and public education school districts. Some states have their own programs, for example in North Dakota, private agencies are contracted to provide the Early Intervention services by region. Other states participate in a national program titled Help Me Grow, which includes over 100 affiliate localized systems, spanning 29 states and Washington D.C. (Help Me Grow National Center, 2020). In the 2019-2020 academic year, 427,234 children ages birth to three were served in the U.S., with increasing rates of participation as children age (https://www2.ed.gov/programs/osepidea/618-data/static-tables/index.html).

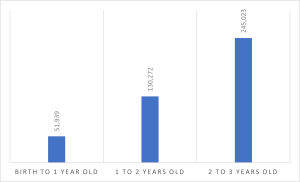

Chart 5.1. Ages of Participants in Part C of IDEA (n=427,234)

Three to Twenty-one

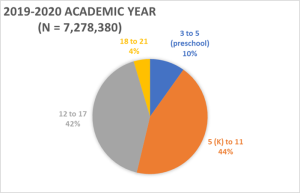

According to the Office of Special Education Programs (OSEP, 2021), approximately 7.3 million children and youth between the ages of three and 21 received services from the U.S. public education system in the 2019-2020 academic year under Part B of IDEA. While services can begin at birth and extend post-high school through the transitions program, most of the children receiving services are considered “school-age,” beginning at the age of five (in Kindergarten [K]) through age 17 (typically high school graduation). Chart 5.1 shows the distribution of children ages 3 to 21 who participated in the U.S. IDEA Special Education programming in the 2019-2020 academic year.

Chart 5.2. Ages of Participants in U.S. Special Education (IDEA Part B) in the 2019-2020 Academic Year (n = 7,278,380)

Some disabled students may not be eligible for services under IDEA and thus would not have an IEP. They may be eligible for a “504 Plan,” which prevents discrimination based on disabling conditions. The 504 plan title is in reference to Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act. One example is that many students who have been diagnosed with mental or other health conditions may have a 504 plan, indicating they may not need specialized instruction. However, this could include accommodations so that they can be successful in school, such as extra time for taking an exam. Nationally, 2.71% of students in grades K-12 are receiving accommodations solely under a 504-only plan (Zirkel & Gullo, 2021). There is significant state variation in the use of 504 plans, with New Hampshire having the highest usage of 6.32%, while Mississippi has the lowest, with 0.65% (Zirkel & Gullo, 2021). These differences are likely due to significant variations in state and local education policies and practices.

Demographics and Disparities

Unsurprisingly, there are significant disparities in who has access to special education services. However, the issue of disparities in special education is quite complex. For example, research studies have shown that BIPOC children will have underdiagnosis in some disability categories, such as Autism Spectrum Disorder, as well as overdiagnosis in other categories, such as Emotional Disturbance (OSEP, 2021), with variations across racial/ethnic and disability categories.

National data shows differences in which students are receiving services under the various disability categories by race and ethnicity. The Office of Special Education Programs (OSEP) has compiled several helpful data charts and tables, including highlighting the racial and ethnic differences of children served by IDEA Part B, among the different disability service categories. This chart shows that White students have the highest rates of service usage for Traumatic Brain Injury. Hispanic/Latinx students have their highest rates of service receipt under the learning disability category and African American students have their highest rates in the intellectual disability category, which happens to be the lowest category for White students (https://sites.ed.gov/idea/osep-fast-facts-looks-at-race-and-ethnicity-of-children-with-disabilities-served-under-idea/). While the OSEP data does indicate that male-identified students have higher rates of Part C participation than female students (4.4 million versus 2.3 million), the data does not further break down by gender regarding specific disability categories. Not surprisingly data is not collected regarding LGBTQ2S status, so comprehensive prevalence rates are difficult to identify for these demographic factors. As many of the diagnoses have at least some biological roots, we can assume that there are many intersectional issues at play regarding child race/ethnicity, gender, and disability category for special education services, including socioeconomic status (Tek and Landa, 2012), and bias in the diagnostic process.

COVID-19 Pandemic

The long-term effects of COVID-19 and larger implications on students with disabilities are beginning to unfold and will be a consideration going forward in how education supports the community. The pandemic undoubtedly affected the distribution of services for students with disabilities. The immediate school closures left any physical school-based service inaccessible, especially as it related to one-to-one support, group, and peer work. The shift to virtual and distance learning had a range of effects on students, and the lack of reliable, adequate, and accessible technology was a point of disparity. Additionally, the stressors of physical, emotional, financial, and familial health impacted the disability community. The National Council on Disability report on The Impact of COVID-19 on People with Disabilities provides an in-depth overview of the effect, specifically Chapter 4 and Chapter 7 (2021). The following are examples of some of the findings (2021, p.145 and p. 197):

- During the shelter-in-place period, many K-12 students with disabilities did not receive FAPE over an extended period of time and went months without essential services and supports that are usually provided in person.

- Children with disabilities in low-income households, and particularly children of color with disabilities in low-income households, experienced particularly severe barriers to remote education during the pandemic.

- While some students with disabilities flourished in the remote learning environment, many students with disabilities struggled to focus and learn through a computer screen.

- Punitive responses to students with disabilities who did not attend or engage in remote education were counterproductive and had particularly dire consequences for students of color with disabilities.

- At all levels including K-12 and postsecondary, students who are Deaf, Hard of Hearing, blind, or with other disabilities faced access barriers in digital platforms and related digital documents.

- Without access to effective mental health supports, including in-person supports, some children with disabilities experienced mental health crises during the COVID-19 pandemic, ending up in emergency rooms, psychiatric hospitals, residential treatment, and even jail.

- Native American students with disabilities served through the BIE received few educational services during the pandemic, effectively losing more than one year of education.

- Due to the social isolation caused by remote work, job loss, closed schools, stay-at-home orders, shuttered businesses, and physical distancing, many adults and children experienced new mental health disabilities or exacerbations of existing ones.

- Rates of anxiety and depression rose significantly, crisis hotlines saw high call volumes, and more people experienced suicidal thoughts.

Learning Activity: Explore this OSEP data, and make comparisons across diagnoses, states, and racial categories.

Providing Services in Early Childhood

Early childhood special education (ECSE) services are provided under both Part C (for children ages birth to three) and Part B (for children ages five through 21) of IDEA. Birth to three services are often provided within the family home, while services for children ages three through five often occur in a preschool setting. In order to be eligible for ECSE, infants and toddlers must meet one of the disability categories as described in IDEA. Many states also include eligibility for young children determined to have a developmental delay, broadening access to crucial early interventions. For example, in Minnesota, young children could either have a diagnosis in one of the IDEA disability categories, or have documentation of a developmental delay score of 1.5 standard deviations from the mean in, cognitive, physical (including vision and hearing), communication, social or emotional, or adaptive development, as determined by a licensed professional (www.mnlowincidenceprojects.org). Any professional with a concern about a young child’s development can refer the family to their local school district to inquire about developmental screening and to assess for eligibility for ECSE.

Individualized Family Service Plan

An Individualized Family Service Plan (IFSP) is a document or case plan that lays out the services and supports that will be provided for infants and toddlers receiving services under Part C of IDEA. It also serves as a contract, holding service providers accountable for ensuring access to and provision of needed services for these young children and their families. An IFSP indicates both the types of services that will be provided, the number of services that will be provided, as well as the goals and interventions that will be used. Services included in the IFSP could be speech and language therapy, occupational therapy, physical therapy, case management services, parenting support, and more. IFSPs are required to be evaluated every six months and are updated at least once per year. A key component of the IFSP is to build off of the strengths of the family, recognizing that young children best receive their growth and development through their families. This differs from an Individualized Education Plan (IEP), as an IEP is a contract for services that will happen in the school setting. Young children receiving special education services in a preschool setting (ages three to five) will have an IEP. More details regarding the IEP are provided later in this chapter. The following is a link to IFSP policy under IDEA: https://sites.ed.gov/idea/statute-chapter-33/subchapter-iii/1436

Advocacy and Justice in Early Childhood Special Education

The broadened eligibility criteria available in some states regarding diagnoses (e.g. a developmental delay category) provide opportunities for crucial early interventions. Scholars from a variety of fields have provided data that shows that early interventions for children with disabilities significantly improve functional and diagnostic outcomes beyond early childhood (Dawson et al., 2010; McConachie & Diggle, 2007; McCormick et al., 1993; Odom & Strain, 2002; Smith et al., 2000). Additionally, services for infants and toddlers are often provided in the home setting, and services for preschoolers typically include transportation to the preschool setting. This reduces transportation barriers present for many families in need of services. Moreover, families do not need access to medical insurance to pay for the interventions, as they are often provided in partnership with the public school system.

Despite this accessibility of services regardless of health insurance status, transportation, and broad eligibility criteria, many young children and their families do not participate in ECSE services. Rosenberg et al. (2008) estimated national IDEA Part C eligibility, based on the Birth Cohort of the Early Childhood Longitudinal Study, and found that approximately 13% of children 24 months of age and younger met the eligibility criteria. However, only 10% of the children eligible were participating in these services. Moreover, it appears that there are extensive disparities in participation rates based on race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status (SES). In an examination of a large representative sample of 4-year-olds in the U.S., Morgan et al. (2012) found that children from families with a low SES, and children living in homes where a language other than English was primarily spoken had lower rates of participation in ECSE. Additionally, studies have found that Black (Morgan et al., 2012: Rosenberg et al., 2008) and Asian (Morgan et al., 2012) children were similarly less likely to participate in ECSE.

Varying explanations for these disparities are found in the research literature. Some authors have highlighted the disparities in diagnoses and participation in early intervention services for children with disabilities who are from families in poverty and children from certain racial and ethnic groups as an accessibility issue, specifically lacking access to health insurance and diagnosis (Liptak et al., 2008). However, other scholars have recognized that many families from racial and ethnic minority groups are aware of their child’s diagnosis, but may choose not to participate in mainstream services such as ECSE, in part due to lack of cultural appropriateness, and may also choose family and peer support instead (Garcia et al., 2000; Eiraldi et al, 2006). For example, Eiraldi et al. (2006) developed a “model of help-seeking behavior” based on research evidence that highlights the cultural factors that contribute to the decision-making of parents from ethnic minority groups regarding service participation for their children with ADHD. This model includes the recognition that cultural norms and values likely carry a stronger weight in service decision-making for families than professional recommendations from outside of the cultural group (Eiraldi et al., 2006).

Due to these known social justice implications of disparities in access and service utilization, social workers and others involved in advocating for families with disabilities should be cognizant of potential issues of systemic racism, classism, sexism, and ableism, and should advocate for historically oppressed groups accordingly. Additionally, since anyone concerned about the development of a young child can refer for developmental screening (including the ability for families to self-refer), early identification and referral to early interventions can significantly improve support for families and potential developmental outcomes.

Box 5.2. Case example, Part 1: Early Childhood

Referral: Maribel Sanchez-Guerrero comes to the attention of the county’s Help Me Grow program staff following a recommendation for services from the family’s physician. The initial phone call for developmental screening comes in from a woman named Luciana, who states that she is a family resource advocate from a community clinic that works primarily with the undocumented Latine population. She states that she is calling on behalf of a mother who does not speak English very well. Luciana provides the following information:

Background: During a well-child visit at the clinic, Carmela Sanchez-Guerrero states that she is concerned about her 2-and-a-half-year-old daughter’s growth and her not meeting developmental milestones. Carmela reports that Maribel has barely begun to speak and has delays in many areas. For example, she did not walk until over age two, and while she can walk now, she seems clumsy and uncoordinated. Carmela also reports that Maribel struggles to hold a crayon and a spoon. The physician recommended that Carmela call Help Me Grow and made in-clinic referrals for both a more extensive eye exam and hearing test since Maribel did not pass either of these screenings during the well-child check. Luciana called Carmela at the physician’s request to follow up on the status of the referrals and offer assistance. Luciana learned that Carmela followed up on the vision and hearing tests, and Maribel has since been prescribed eyeglasses and has also been diagnosed with a mild hearing impairment and received a referral for a specialty clinic to assess for hearing aids. Carmela tearfully tells Luciana that she has not scheduled the additional hearing test and she did not contact Help Me Grow because they are not documented and she was concerned about being reported and not being able to afford any of the services. Carmela stated that she trusted the community clinic, but felt very anxious about reaching out to other programs or clinics because she had a cousin who was deported following an attempt to get public benefits. Luciana states that she assured Carmela that the Help Me Grow program was provided in partnership with the public school system (IDEA, Part C), and that seemed to reassure Carmela, as she states that she has an older son who is in the local public school and that it has been a positive experience, and they have felt safe. She asks Luciana for assistance with the calls due to her limited English.

The Sanchez-Guerrero family consists of Jorge Guerrero, age 30, who is employed by his cousin doing home siding and roofing; Carmela Sanchez-Guerrero, age 25, has worked in food service occasionally, but is primarily staying home with the younger children; Diego Sanchez-Guerrero, age 7, attends first grade at the local public school and appears healthy; Maribel Sanchez-Guerrero, age 2 and a half, presents signs of developmental delays in gross motor and fine motor control and speech. She also has a hearing impairment; Mateo Sanchez-Guerrero, age 13 months, appears healthy; Carmela also reports that she is about 5 months pregnant and that the pregnancy is going well. The parents report that they came to the U.S. for work 3 years ago when Carmela was pregnant and Diego was 4. Maribel was born in the U.S. They live in the lower part of a home owned by Jorge’s cousin who is his employer. The two families help one another, and it seems to be a stable and supportive, although crowded, living situation.

Part 1 Discussion questions:

- What social justice and disability justice issues are present?

- Apply the practice model from Chapter 2, with an emphasis on

- The pre-engagement stage: consider issues of anti-oppressive practice, intersectionality, and critical cultural competence.

- The engagement stage: Which issues and strategies will be important to consider in beginning work with this family?

Providing Services for School-Aged Children and Youth

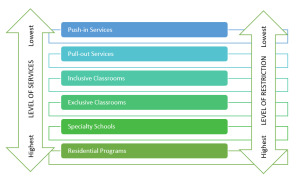

School-aged children and youth can receive a variety of disability services and supports, in a variety of settings. These supports are not exclusively tied to a classroom or physical location within the school, as services are intended to be highly individualized to each student’s needs. There are six main levels of support (see Chart 5.3). Beginning with the lowest level of intervention, “Push-in services” involve a specialist (such as an occupational therapist or speech and language therapist) coming into the classroom to provide support to the teacher during designated regular instruction times. “Pull-out services” involve pulling the student out of class to work with a specialist individually or with a group for a designated period of time, such as a speech therapy session or social skills group. “Inclusive classrooms” are settings that have a mix of typically developing and disabled peers, with needed services and supports embedded into the classroom. “Exclusive education classrooms” typically involve a smaller classroom that is encompassed of children receiving special education services, with a lower student-to-teacher ratio to provide students with the levels of support that they need. “Specialty schools” are entire school settings that are designed specifically for children with disabilities, and sometimes a specific disability. These specialty schools can be public schools, charter schools, or private. The most restrictive educational settings for children with disabilities are “Residential programs.” These programs are for children who need 24-hour care and services, and who would not have their needs met in a community setting. Due to the intense level of services, we discuss residential programs in more detail later in this chapter, including some of the associated controversial and ethical issues.

Chart 5.3. Levels of Special Education Support

Individualized Education Plan

Like an IFSP, an Individualized Education Plan (IEP) is a document that dictates the services to be provided, the goals, and methods by which to attain those goals, including the level of services and supports that are to be provided. IEPs hold school districts accountable for providing these services and serve as a contract. An IEP is required to be reviewed on an annual basis. However, the review can happen more frequently at the caregiver’s request. All service providers, parents/caregivers, case managers, teachers, and school district representatives are all invited to attend, as well as the children themselves at the age of 14 and older (by law), with many teams including children at much younger ages. Children are re-evaluated at least once every three years.

While the IEP is intended to be a collaborative process, many times the involved parties do not agree. It is important for social workers to hold true to the professional values of client self-determination, as well as person-centered and family-centered practices. Parents and disabled youth who do not agree with the plans set forth by the school are entitled to “due process” via the IDEA legislation. Families and schools that cannot come to an agreement on their own can enter this mediation process, which needs to be initiated by the parents/caregivers, who file a complaint with their local/state department of education. There are deadlines and specific processes that need to be followed, and social workers who are working with disabled children and their families (whether as school social workers or as advocates) should be aware of this process, and always advocate for the best interests of the child and family. More information on the IDEA legislation in regards to due process complaints can be found at the next website https://sites.ed.gov/idea/regs/b/e/300.508, and some helpful information for parents and caregivers regarding their rights and advocacy (including sample forms for requesting a due process hearing) can be found at The PACER Center: https://www.pacer.org/learning-center/dispute-resolution/due-process-options/due-process-complaints-and-hearing.asp.

Box 5.3. Case example, Part 2: Early school-age

Maribel Sanchez-Guerrero is now 9 years old and in third grade. She has been attending the community elementary school that her older brother Diego had attended (who is now 13 and in middle school), as is her brother Mateo (age 7, 1st grade), and brother Marcos (age 5, Kindergarten). Maribel has an IEP, and is in a mainstream classroom with supports, with occasional pull-out to the special education room to complete work. The school social worker has been exploring reports of teacher concerns over this past school year, and is planning assessments for alternative diagnoses, level of care and supports.

Background: Following the initial in-home supports and services provided via Help Me Grow, Maribel attended a special education preschool program offered in their school district for children ages 3 – 5 (IDEA, Part B). She attended this program for 2 years prior to entering kindergarten, and did well in the program. She was well-liked by the teacher and aides, and also received several services in the preschool class setting, including speech and language therapy, physical therapy, occupational therapy, and audiology. The audiologist was able to help the family get connected with hearing aids for Maribel, and she gained strength and a lot of gross and fine motor skills. Maribel thrived on the schedule and routine, and often reminded the teacher of the schedule. She transitioned to kindergarten with ease, as she had grown to love the school routine from her preschool experience. She developed a particular interest in books, which was nurtured and encouraged both at home and at school – especially books about horses! Because of her quiet nature, adherence to routines and schedules, and her love of books, Maribel did well in kindergarten, first and second grade. Her primary diagnosis for her IEP is her hearing impairment, and she is also continuing to receive speech therapy and occupational therapy.

Current concerns: Challenges began to arise in the transition to third grade. Teachers and aids have reported that Maribel appears to be struggling to pay attention and seems withdrawn. She has a somewhat flat affect, and only appears to be engaged and interested when it is reading time. While Maribel continues to adhere to the routine and schedule of the day, she seems generally uninterested and has had a few outbursts (screaming, punching the desk or wall, pulling her own hair) when she has been pushed by adults to become more engaged. She does not have many friends, although was well-liked by her classmates up until the more recent challenges. She did have one close friend who has been pulling away from Maribel, stating to the teacher that Maribel is babyish as she still only wants to talk about and play horses instead of tag and soccer with the other kids. School

staff had suggested that Maribel may have ADHD (inattentive type) or perhaps depression, however the school social worker suspected Autism, as they had recently attended a training about Autism in girls, and how it can present differently from boys and often goes hidden and undiagnosed until later than boys. This suspicion proved correct, and Maribel was given a school diagnosis of Autism, with a recommendation for more specialized services.

Part 2 Discussion questions:

- What new disability justice issues have arisen in this case at this stage?

- Where are some of the missed opportunities for service provision? How could things have been done differently/better?

- Apply the practice model from Chapter 2, with an emphasis on

- The Assessment stage

- The Intervention stage

504 plans

Students covered under IDEA are simultaneously protected by section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act. However, many students who do not qualify for special education services under IDEA still benefit from a 504 plan. Since IDEA requires that students both meet the diagnostic criteria and need special education services, some children who need accommodations but do not meet the IDEA definition standards could fall through the cracks. Students who have health conditions such as diabetes or food allergies, mental health diagnoses, and mild ADHD can receive accommodations via a 504 plan such as allowance of increased breaks or visits to the nurse’s office, use of pre-approved fidgets, specific seating arrangements that reduce distractions, and homework and/or testing modifications, as well as protections from discrimination for needing to use these accommodations.

Within over 1.3 million children who receive services solely under a 504 plan, there is evidence that these students are overwhelmingly male, and White (Zirkel & Weathers, 2015). Moreover, there is significant state variation in the use of 504 student protections, ranging from less than 1% to almost 7% (Zirkel & Gullo, 2021). Thus, social workers working with children and youth should advocate for full and equitable access to protections offered by Section 504.

The controversy of mainstream/inclusion versus disability-centered rooms and schools

Many advocates call for full inclusion of children with disabilities in mainstream educational settings, arguing that it is more socially just to give disabled children access to everything that their non-disabled peers have and to support and encourage full acceptance and inclusion of disabled children into the community. A key point of this viewpoint is that separate schools are segregated schools, which violates the right to a free and appropriate public education in the least restrictive environment as stipulated by IDEA (see the 2018 report by the National Council on Disability titled The Segregation of Students with Disabilities here: https://ncd.gov/sites/default/files/NCD_Segregation-SWD_508.pdf). However, other advocates counter that some children with disabilities thrive best when in an environment designed specifically to meet their needs, versus forcing inclusion within systems that are ableist in their inception and design. Advocates of this approach are generally referring to a specific subgroup of disabled youth who would be considered to have a greater level of impairment from their disability, and thus require a higher level of supports and services. These advocates argue that the term “specialized” education is a better term to use than segregated, as it creates an accepting environment full of services and specialists, which supports disabled students feeling welcomed, wanted, and better able to develop relationships due to the presence of a true community of peers. Read one dad’s take on this perspective here: https://www.disabilityandemployment.net/2019/01/07/why-i-support-segregated-schools/.

The role of the school social worker

School social workers are employed by the school district and provide a variety of services within the education setting. School social workers work along the micro-to-macro practice continuum, working directly with students, parents and families, school personnel, and school districts, and connect to resources within the broader community. School social workers provide direct services, including crisis intervention, counseling, social skills groups, assisting families to connect with school and community resources, conducting student assessment, and providing support to staff. They also provide many indirect services, such as participating in IEP meetings, special education case management, planning training programs for school staff (i.e. anti-bullying, suicide screening and prevention), provide consultation regarding school policies, and address attendance concerns (School Social Work Association of America, 2021, www.sswaa.org).

Education in Residential Settings (a Deep and Critical Dive)

According to the OSEP data, 13,725 children with disabilities received their education in a residential setting during the 2019-2020 academic year (OSEP, 2021). While this is less than 1% of the total students receiving services in the various education settings, due to the abundance of potential social justice issues, as well as the high likelihood of intersection with social workers, this topic deserves some special attention.

History of Residential Settings

The inception of residential settings arose from the intersection of several institutions; state government, carceral system, faith-based charities, and education (Richardson and Parker, 1993, p.364). Each of these institutions have upheld a specific framework, i.e. white supremacist/colonist ideology, of who is “worthy” of resources, access, and ultimately deemed a “person.” This ideology holds especially true in the creation, functionality, utility, and treatment of children enrolled in residential schooling. The beginning of these residential school settings occurred in the early 1800’s initially for children, “considered indispensable” who were blind, visually impaired, deaf, hard of hearing and/or hearing impaired, and “were all marked by the common need of specialized guidance and adjusted educational procedures” (Martens, 1940, p.1). These were “welfare institutions designed to give care and training to those with serious handicaps appeared to make institutional care necessary” (Martens, 1940, p.3). It is essential to situate the development of residential schools within the political context as education institutions are typically one of the first spaces to mirror the current circumstances. During this time, the dehumanization of those deemed “disabled” was acceptable and in the 1860’s written into municipal statutes, known as the “Ugly Laws.” This outlawed the appearance of those who “diseased, maimed, mutilated and or deformed, as to be an unsightly or disgusting object” and this undoubtedly intersected with the education system in the choice to send disabled children away to school, versus inclusion in school with non-disabled children (Wilson, 2015).

Additionally, in the mid-1800’s the rise and government implementation of residential boarding schools inflicted a wave of violent assimilation and acts of genocide on Indigenous communities across the country in efforts of “civilization” (Keating, 2016). It wasn’t until 1862 that the Emancipation Proclamation prompted the end of slavery, in which Black communities who were enslaved and free were still intentionally excluded from these spaces, unless there was crossover into carceral system specifically referrals to “state reform or industrial schools” (Richardson and Parker, 1993, p.364). Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarashinha provides a larger perspective to the realities that BIPOC communities were experiencing and the means for survival that were not tied to state organized and endorsed systems.

for many sick and disabled Black, Indigenous, and brown people under transatlantic enslavement, colonial invasion, and forced labor, there was no such thing as state-funded care. Instead if we were too sick or disabled to work, we were often killed, sold, or left to die, because we were not making factory or plantation owners money. Sick, disabled, Mad, Deaf, and neurodivergent people’s care and treatment varied according to our race, class, gender, and location, but for the most part, at best, we were able to evade capture and find ways of caring for ourselves or being cared for by our families, nations, or communities — from our Black and brown communities to disabled communities (2018, p.38).

The historical context here has undoubtedly influenced the structure of residential schooling for those with disabilities or those societally labeled as “disabled” and who have received access to these spaces. Regardless of the societal perspective of residential schooling, the creation and sustained operation of these spaces was the initial step to creating access to education and care for disabled children, who were often outcast from their community, family, and shared spaces. Arguably, these residential settings did provide more community for those with similar experiences, tailored education, and an opportunity not possible before. In addition, residential schools were also created for those “mentally deficient” and “socially maladaptive/juvenile delinquent” (Martens, 1940, p.63, p.83). It is important to note that the use of language here is now outdated. The 18th and 19th century reform movements and medieval church valuing “charity” created “health services for children” which included “orphanages, hospitals, homes, asylums, and later in the early 20th century psychiatric facilities” for those who were “poor, retarded, sick and mentally ill” (Leitchtman, 2006). This vastly expanded the variety of residential settings that children, adolescents, and young adults with disabilities encountered when trying to access care, education, or forced to comply with society’s expectation of invisibility. It was not until the Education for all Handicapped Children Act of 1975 that instituted a federal mandate for inclusivity, accommodation, and access to education for children with disabilities (see other sections in this chapter and text for more details on this policy). Despite this federal policy, the implementation varied across states, counties, and communities for guaranteeing access to education, fueling disparities and intersystem interactions, i.e. education, carceral, and medical care complexes. This is still quite present today.

Decision-Making Process

In the 1800s-early 1900s, the process of enrolling or simply sending a young person to these institutions for schooling was fairly straightforward as there were literally no other options. However, access was likely not equal across race and ethnicity. Segregated schools were established, such as the Texas Deaf, Blind, and Orphan School for Colored Youth, which was established in 1887 (Markham, 2020). Yet, the inclusion of disabled students from various racial and ethnic backgrounds in these residential schools may have been more progressive than public schools, as some schools for the Deaf and Blind were integrated, including both White and Black students as early as the beginning of the 20th century. For example, the St. Augustine School for the Deaf and Blind, which opened in 1885, graduated its first Black student in 1914 (African American Registry, 2022).

The shift in policy, political climate, the deinstitutionalization movement, and community activism (see Chapters 9 Behavioral Health Care and Chapter 14 Disability Civil Rights Movement) led to Wyatt v. Stickney in 1971, which “decided that people in residential state schools and institutions have a constitutional right to receive such individual treatment as would give them a realistic opportunity to be cured or to improve his or her mental condition. Disabled people could no longer be locked away in institutions without treatment or education” (Southern Adirondack Independent Living, 2018). The shift away from institutionalization especially with those with psychiatric disabilities was “contrary to the original intent of moving people out of institutions, smaller versions of highly supervised, regulated, and to a large extent, segregated residential environments trapped residents in a kind of trans-institutionalization” (Farkas and Coe, 2019, p.2).

There was no clear policy that ensured education in residential settings until 1975 (see the section on the Rehabilitation Act of 1975), and even so, the implementation varied due to state control, which then often referred to the district, then again referred down to the facility themselves. The Department of Education is to be the “governing body,” but the implementation of access was not further solidified until 1990 with the passing of IDEA. These structures are important to consider as it relates to the practice of the school, families, and other systems involved or absent in the placement process. This is a highly debated process, as heavily influenced by individuals or systems, who have the power, authority, and legality to make the serious decision (given the array of services available in the community) of removing a child from a community setting.

These removals were previously “justified on the basis of community protection, child protection and benefits of residential treatment,” (U.S. Surgeon General, 1999, p.170), but lacking research consistent with their effectiveness, even though they were “widely used but empirically unjustified services” (Hoagwood et al., 2001, p.1185). During the 1990s, skepticism arose due to the overuse of residential facilities and proposed that community settings “such as day hospitals, family preservation programs, wraparound services, and multisystemic treatment” were more appropriate, especially as increased medication use reduced some of the more serious symptoms (Baldessarini, 2000, as cited by Magellan Health Services, 2008, p.3). Given this context, the decision-making process has become increasingly important and layered in ensuring the autonomy, independence, health, safety, wellness, and education of the individual. The right to self-determination, the inherent dignity and worth of a person, as well as a least restrictive environment, are priorities in this process, especially for caregivers and individuals without disabilities who are involved in decision-making with and for minors with disabilities.

Abbott, Morris, and Ward discuss the whole placement process experience from the family and student perspective. Overall, there is a somewhat unclear process in the collaboration between residential-setting and community-education staff, health care providers, assessors, and correctional setting professionals (depending on circumstance) working with families or the young people themselves (2001). See Table 5.1 below, highlighting Abbott, Morris, and Ward’s summary findings about perspectives in the decision-making process (2001).

Table 5.1. Perspectives of Residential Placement, from Abbott, Morris, and Ward’s findings (summary, 2001).

| Negative Perspective | Ambivalent Perspective | Positive Perspective |

| “homesick”

“Nervous” “uncertainty” “avoidant about the process” “not a preferred option” “difficulty decision” |

“mixed feelings about being placed in residential setting”

“delayed timeline for placement” “process included those who have no interaction with young person/student” “lack of transparency in the process, regulations, and communication with the child once in residential setting” |

“excited to potentially make friends”

“more independence” |

Overview of Services and Education in Residential Settings

The care received varies based on the specific population, needs, identities, and collective community within the setting. Additionally, the structure, operation, regulation, and funding for these facilities can influence the quality and/or quantity of care and education. Specifically, there is more research available about treatment, care, and education. Generally, “more is known about the behavioral and mental health functioning of children in care. Little research has been conducted on the academic functioning of children in residential care and even less on children with disabilities in this population.” (Trout et al., 2008, p. 126). Additional factors influencing this placement could be “histories of family instability; substance, sexual, and physical abuse; neglect; high-crime neighborhoods; poor social supports; and frequent out-of-home placements. Many of these children present significant behavioral, mental health, and educational problems that require treatment while in care” (Trout et al, 2009, p. 112). These influences also mirror the intersections of the child welfare system, carceral state, and medical complex, with undoubtedly disproportionate and detrimental long-term effects for the disability community.

Residential, congregate, and group care settings are “theoretically intended as a placement of last resort, and as a response to characteristics or psychosocial problems that cannot be addressed in less restrictive family-based settings” while community-based options have more concrete evidence as being an effective form of care, treatment, and education (Barth, 2002 as cited by James, 2012, p.1). There are legitimate risks associated with the placement due to systemic influxes and circumstances such as “staff with often inadequate training and high turnover rates, issues of safety, and potential for abuse as well as negative peer processes” (e.g. Burns et al., 1999; Dishion et al., 1999 as cited by James, 2012, p.2). In addition to decreasing these risks, the following elements are necessary for effective treatment within residential settings : “family involvement (both in the family-centered approach but also close physical proximity to access the residential setting), Placement Stability and Discharge Planning (start at the time of admission, knowing what is needed in community) and Community Involvement and Services (facilitated community connection while in residential treatment and availability, accessibility, and appropriate supports for individual and family)” (Magellan, 2008, p. 6-7). There are circumstances in which these settings are beneficial to individuals and their families, whether a short, interim, or long-term duration. Magellan states there are decades of evidence that demonstrates “there are effective alternative community-based services for those children who can safely be treated at home” (2008, p.2). Additional resources that are alternative to residential settings include “therapeutic foster care, multidimensional treatment foster care, therapeutic group homes, case management, wraparound, multisystemic therapy, assertive community treatment, mentoring” and also community care networks. (Magellan, 2008, p. 8-10). Some of these treatments and supports, children have experienced prior to residential placement and could have been deemed inappropriate at the time. The needs, wants, and trajectory of every individual is continually changing, but it is crucial for resources, opportunities, and choice to reflect that adequately.

Controversies in Residential Settings

Given the functionality, use, and appropriateness of residential and community settings, there are many controversies, gray areas, and ethical dilemmas that may arise. The following are a few examples to consider when evaluating the intersection of disability, education, social work, and social justice:

- There is a clear balance between upholding two different requirements of IDEA: “the most appropriate setting” and the “least restrictive environment.” The details within these definitions are individualized and based on how that shows up for each child. Additionally, it is reliant upon the resources that are available within the community, and the financial, logistic, and practical accessibility of that resource. Residential settings are often more focused on the disability and the related treatments, responses, and therapies (often prioritized due to heightened needs) than on educational pieces, which is cause for controversy.

- There can be a large difference between considering the power, authority, rights, and wellness of the caregiver and the child (which may differ, interfere, or jeopardize the other). This is especially heightened regarding the voluntary or involuntary nature of the residential placement or community-based options.

- The current use of shock and aversive therapy. Opponents of this approach draw attention to practices that are arguably inhumane, including the use of a graduated electronic decelerator (GED), in which electrodes are attached to the child’s legs and arms for up to 24 hours a day, with a device in the control of the paraprofessional/medical provider, with the ability to administer a shock to “correct” and “modify” an undesirable behavior (McFadden et al., 2021). There is a plethora of evidence ranging from 2012-2019 of the negligence, inconsistency, and abuse that these devices inflict on students who may have intellectual, developmental, and emotional disabilities that affect their communication, decision-making, and cognition, which certainly amplifies the controversy around this treatment (McFadden et al., 2021). Additionally, these young people may come from histories of abuse, neglect, and physical punishment for their own existence, identity, and disability.

- Applied Behavioral Analysis (ABA) is a long-standing, widely used, and fairly controversial behavior-based intervention used on children with disabilities. ABA originally founded in 1970 by Ivan Lovah and Robert Koehler, “is a scientific discipline that essentially involves the application of techniques that are based on the principles of changing the behaviors to what is socially acceptable (Understanding ABA, 2019 as cited in Dhawan, 2021, p.381).” The manner in which this is done is heavily focused on the consequences of the behavior and repetitive corrective responses to changing what is deemed as “socially unacceptable.” There is a history of punitive and physical forms of “correcting the unwanted behaviors,” and there has been a shift in utilizing reward-based systems for behavioral intervention. The following site provides an overview of ABA and the advantages About ABA – MyABA Today. The following video from Chloe Everett, a neurodivergent individual, provides her own perspective on the history and current ramifications of ABA. The Problem with Applied Behavior Analysis | Chloe Everett | TEDxUNCAsheville – YouTube

Advocacy and Justice for School-Aged Children and Youth

There are several important social justice issues and concerns for disabled school-aged children and youth in the educational system. While not an exhaustive discussion of all of these issues, some of these topics will be discussed below.

The disproportionate number of children of color in the U.S. Special Education system

Students from all racial/ethnic groups, other than Asian students, have higher rates of participation in special education than White students. One theory for why this disproportionality occurs is that students of color may actually have higher rates of disabilities than their White peers, due to a variety of factors related to intersectionality, SES, and Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs). Additionally, there is evidence of systemic racial bias, resulting in students of color being identified as disabled in ways that differ from White students (National Center for Learning Disabilities, 2020).

An additional concern is the patterns of disproportionate use of some diagnoses in certain populations, referred to as diagnostic bias, for example, assigning African American males with conduct disorder and their White male counterparts with a mood or anxiety disorder for similar behaviors (Mizock & Harkins, 2011). This phenomenon can take place within the U.S. education system as well, and is not a problem with the IDEA policy as it is written, but rather a problem with implementation and systemic racist practices within the diagnostic labeling process.

Disparities in Discipline Practices

Another significant issue of concern for social workers is the glaring evidence of systemic racism with discipline practices for students with disabilities, and in particular, disabled students of color. Discipline disparities take the form of harsher punishments for similar behaviors, including suspensions and expulsions. While there is evidence that discipline disparities are present for all BIPOC children and youth in the education system, the disparities are even more stark for BIPOC children with disabilities. Research evidence shows that Black males from low SES households who are in special education are suspended at the highest rates of any group. The causes of these disparate practices are layered, intersecting with systemic racism, teacher bias, and SES (National Center for Learning Disabilities, 2020). Additionally, emerging research shows that Black girls are disciplined at rates 6 times that of White girls, and were suspended at rates significantly higher than boys (U.S. Department of Education, 2014). This speaks to the intersections of race, disability, and gender in school discipline practices.

The U.S. Department of Education, Office for Civil Rights (OCR) presented the following Data Collection in June 2021: Exclusionary discipline practices in public schools, 2017-18 (PDF) (ed.gov). It is important to note that this data presented is from 2017-2018, which is before the global COVID-19 pandemic, which has undoubtedly affected the education system. The Civil Rights Data Collection includes data on public education ranging from pre-K through 12th grade in all 50 states, D.C. and Puerto Rico. Education settings in this data include: “charter schools, alternative schools, juvenile justice facilities, and special education facilities, and school district data at large” (OCR 2021, Slide 2). The total number of students attending public schools was 50.9 million, and students with disabilities make up over 8.1 million (15.9%) of the total population (OCR, 2021, Slide 3). Overall, there was a 2% decrease in disciplinary actions, but “increased discipline practices of 1) school-related arrests; 2) expulsions with education services, and 3) referrals to law enforcement” (OCR, 2021, Slide 4). This relates to a concept referred to as “the school-to-prison pipeline,” which is discussed below. Students with disabilities who are receiving services under IDEA “represented 13.2% of the total student enrollment and received 23.3% of all expulsions with education services and 14.8% of expulsions without education services” (OCR, 2021, Slide 13). The disparities grow wider as disability intersects with race and ethnicity, as “Black students served under IDEA accounted for 2.3% of total enrollment, but received 6.2% of one or more in-school suspensions and 8.8% of one or more out-of-school suspensions” (OCR, 2021, Slide 19). Furtado et al. further state that these disparities are of heightened concern because “the way we enforce rules and assign penalties like OSS (out-of-school suspensions) is not effective at preventing future misbehavior, and the cost of discipline gap lies in the billions of dollars in lost education time, increased risk of incarceration which leads to diminished productivity and income long into adulthood” (2019, p.5).

Caregivers of children with disabilities and social workers should be aware of the special rules regarding discipline and children with IEP’s, which differ from children without an IEP in place. Children with IEP’s have some extra protections regarding discipline practices, as many behaviors that rise to the level of requiring discipline are actually manifestations of the disability itself. One example is impulsive behaviors that may be aggressive, yet the child in question is receiving services for Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder, Impulsive Type. Children with IEP’s can still be disciplined and even suspended. However, this generally cannot exceed 10 days in a row (and in some cases within a given school year), or it is viewed as a change of placement. More information on these special rules, including advocacy tips for caregivers can be found at Kidlegal.org: https://kidslegal.org/special-education-discipline-suspensions-and-expulsions

School to Prison Pipeline